Aqua Civica

Aqua Civica

Urbanising cities in the global south struggle to be inclusive of settlements inhabited by poor communities that cannot afford market based ownership or rental properties. In India, they have to negotiate occupancy rights politically, a negotiation that places them in a state of uncertainty as legitimate citizens and deprives them of access to basic civic infrastructure. Their homes are referred to as slums, a label that implies informality and contrasts with the “legitimate formal” city. Their struggle manifests itself most acutely in daily life - often in the form of accessing basic necessities, especially water supply.

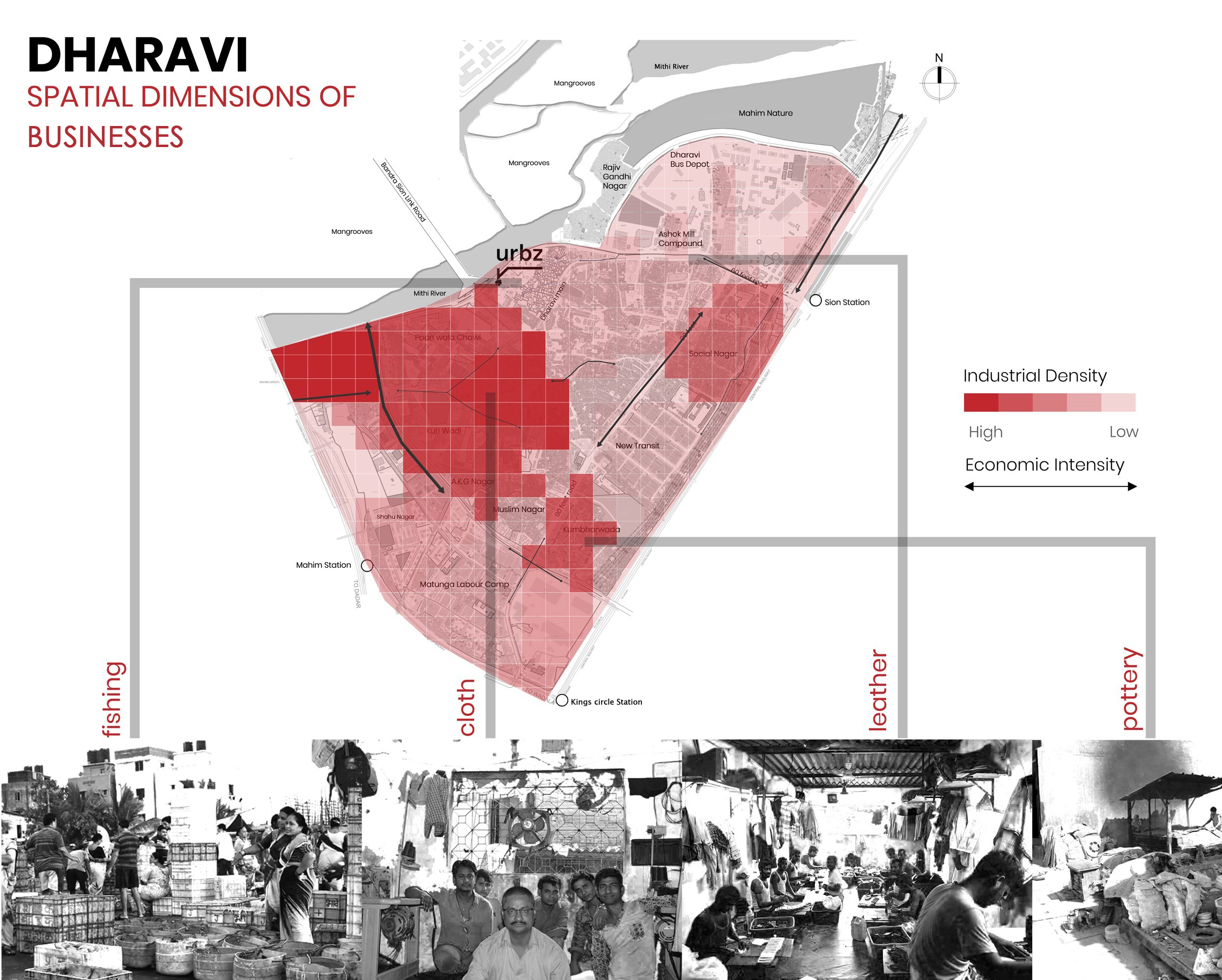

Dharavi in Mumbai, India, is popularly known as “Asia’s largest slum”, a moniker that belies the more nuanced reality of its residents. We coined the phrase “homegrown settlements” to describe such neighbourhoods that are built from within by people who live and work in them. Dharavi emerged around a fishing village of the aboriginal fisherfolk of Mumbai - the Koli’s, whose settlements - Koliwadas - dotted the coast of pre-colonial Mumbai. The Kolis of Dharavi inhabit a delta landscape on the banks of the Mithi River and depend on it to farm fish; they negotiate the urban river to continue these traditional activities. Dharavi Koliwada has been coping with annual water logging, making the community vulnerable yet most primed to adapt to the vagaries of climate change. While officially classified as urban villages, Dharavi Koliwada, like other Koliwadas were and still get treated as slums. Their life continues to be an attempt at bridging the gap between illegality and legality, formality and informality.

The Dharavi Koli Jamat, an organisation that represents the residents of Dharavi Koliwada, has taken the first step by planning a new water supply and sanitation system for the community. Until now, the residents were left to their own devices. As per their need, each household drew its water supply lines, creating a dense network that grew incrementally, adding to the maze of pipes headed to the main municipal pipe. Sanitation infrastructure became intertwined with this maze, with sewage frequently contaminating the water supply lines and putting the residents at risk of water-borne diseases. This is what necessitated the creation of the new community led plan.

urbz has started working closely with the Dharavi Koli Jamat to plan and design an intermittent secondary water and sanitation system between the Municipal supply and each household. This system will streamline the supply and sewage channels and allow easier access for maintenance. Once implemented, it will provide safe access to fresh water and sanitation to about 5,500 people of Dharavi Koliwada, which includes 300 migrant families along with 370 Koli families. It is an integrated solution by the indigenous community. While such a system will definitely improve the physical quality of the infrastructure, it also represents a strong symbolic move towards legitimacy, asserting the community’s presence in the city’s civic landscape. The project also has the potential to scale up in other Koliwadas and homegrown neighborhoods of Mumbai and beyond.

The immense potential for processes that improve civic infrastructure to act as a tool that communities can use to overcome their marginalisation must not be ignored. Community projects, especially ones that improve water supply and sanitation have more benefits than what is obvious, they can also be vehicles to politically assert urban citizenship and bridge growing iniquities.