Communidade and a transforming Goa- impact of tourism

Communidade and a transforming Goa- impact of tourism

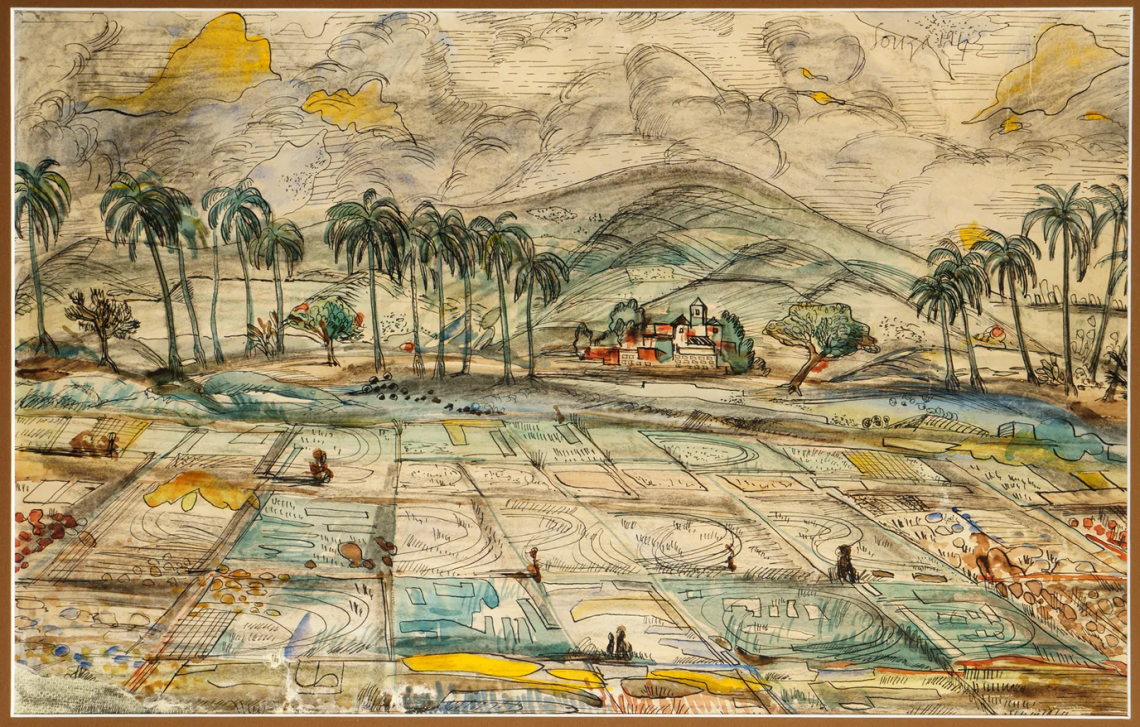

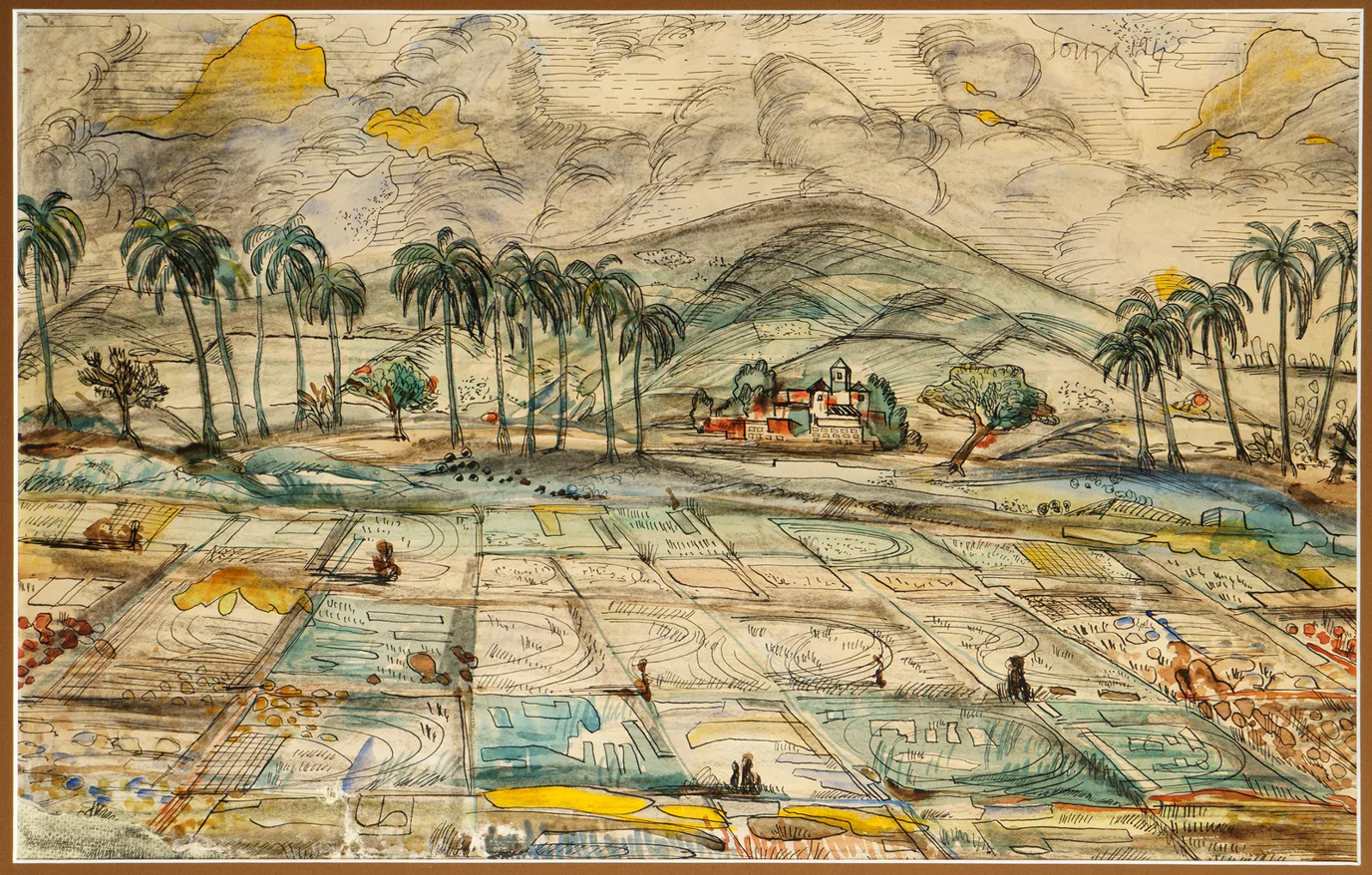

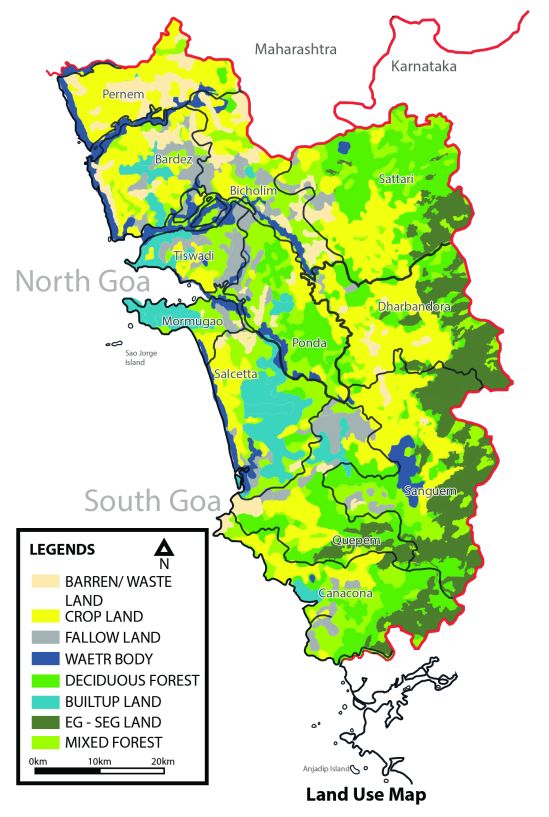

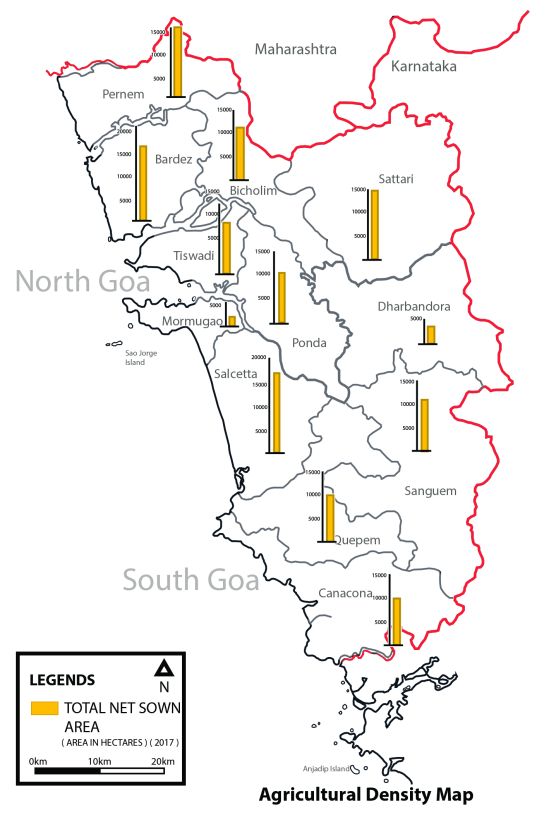

Economic growth and social changes are major factors contributing to Goa's urbanisation. Today the Goan economy is hugely dependent on tourism. Its distinctive lifestyle and cultural blend attract many from the rest of India and abroad. While the domestic tourist, comprising 80% of all tourists, comes to Goa to experience a different culture, “international tourists visit Goa purely for the natural environment, the sun and beaches.” (Sawkar 1998) These tourists also look for a more “local and variegated experience”. (Noronha 2002) Tourism became the key sector in the development of Goa due to its potential in generating income. The seasonal nature of the tourism industry has opened doors for employment, especially among unskilled workers. Tourism was also preferred over industrial development and mining as it was comparatively perceived as less polluting. However, a lack of “awareness and understanding existed back then among planners about the processes of the life support systems of the coastal environment and the interactive roles played by each component.” (Noronha 1998) Tourism began expanding along the coast rapidly and uncontrollably. There is a visible burden on the infrastructure and environment such as the coastal aquifers, dunes and mangroves.Tourism has promoted urbanism and drastically changed land-use patterns.

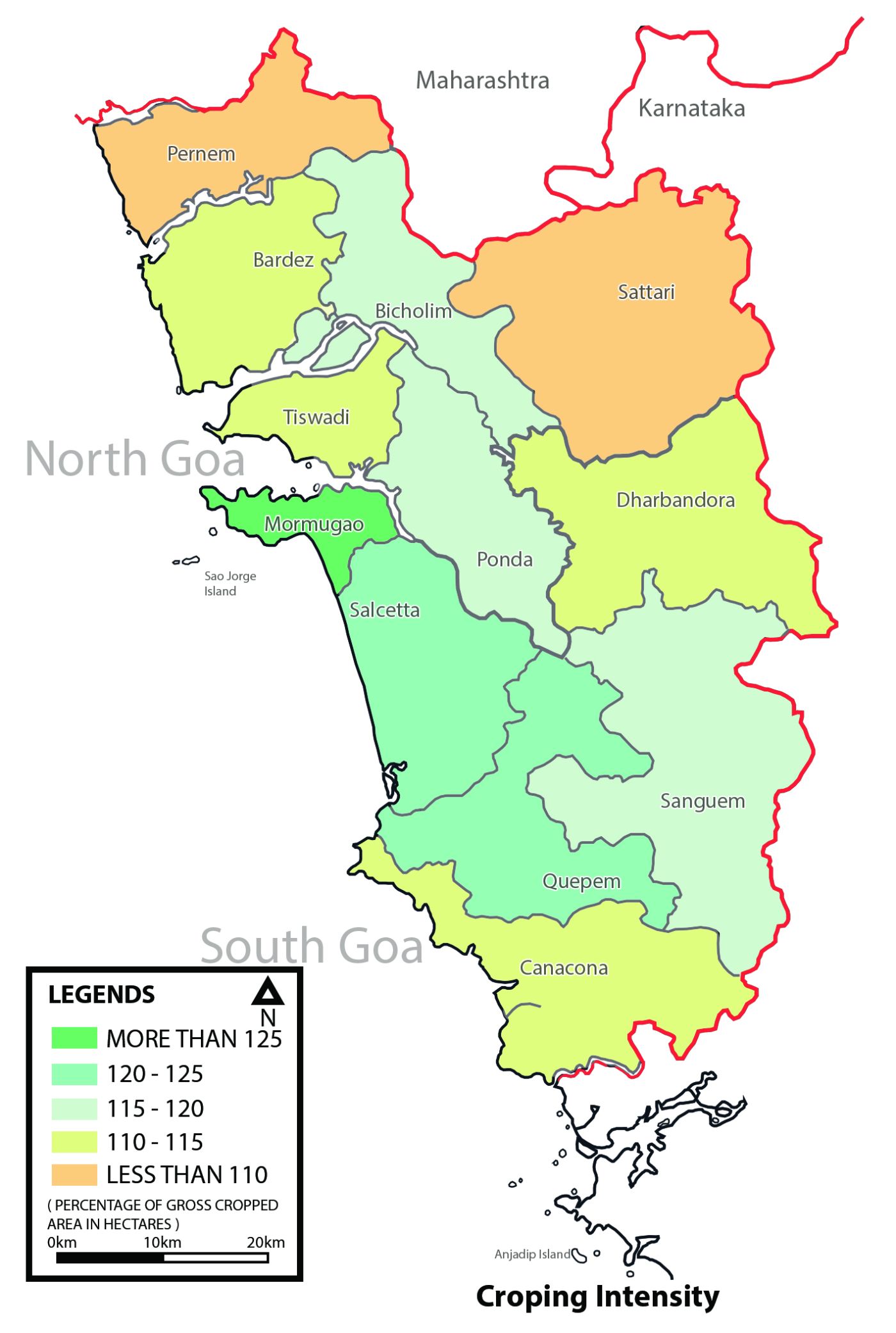

Historically the Goan village lands were divided into three categories based on productivity.

1. Gaunkaria Lands

“The largest and most productive, called Gaunkaria land, was annually or biannually auctioned among the gaunkar households and used for their livelihood and private interests.” (Jacob 2019)

2. Devachebhat or God’s Land

“The second type known as Devachebhat or god’s land was used to cover costs arising from religious expenditures – maintenance of temples, the livelihood of priests, temple servers and performance of rituals of the village as a whole.” (Jacob 2019)

3. Communal Land

“The last type was the communal land reserved for specific products such as the Khazans. The Gaunkars were recognized as the only rightful collective owners of the communal lands. However, the communal land was also leased to a Mundkar and its earrings were used for village clerks, artisans, labour force to name a few. The earnings from the land were used to finance public works and generate additional income for the village community.” (Jacob, 2019)

“A survey conducted around 1961 indicated that the Comunidades owned 34.9% to 85.5% of the cultivable land in Goa. They owned 200-400 hectares of land in the coastal tracts and 2-40 % of 14,968 hectares of land. At the time of liberation, an average Comunidade distributed 16 % of its earnings as dividends. They spend 22 % on administrative expenses, 19 % on land tax or quiet rent, 16 % on extraordinary expenses, 6 % on religious and social work, 2 % on the amortisation of loans and payment of interests and 19 % on miscellaneous expenditures” (D’Cruz, 2005).

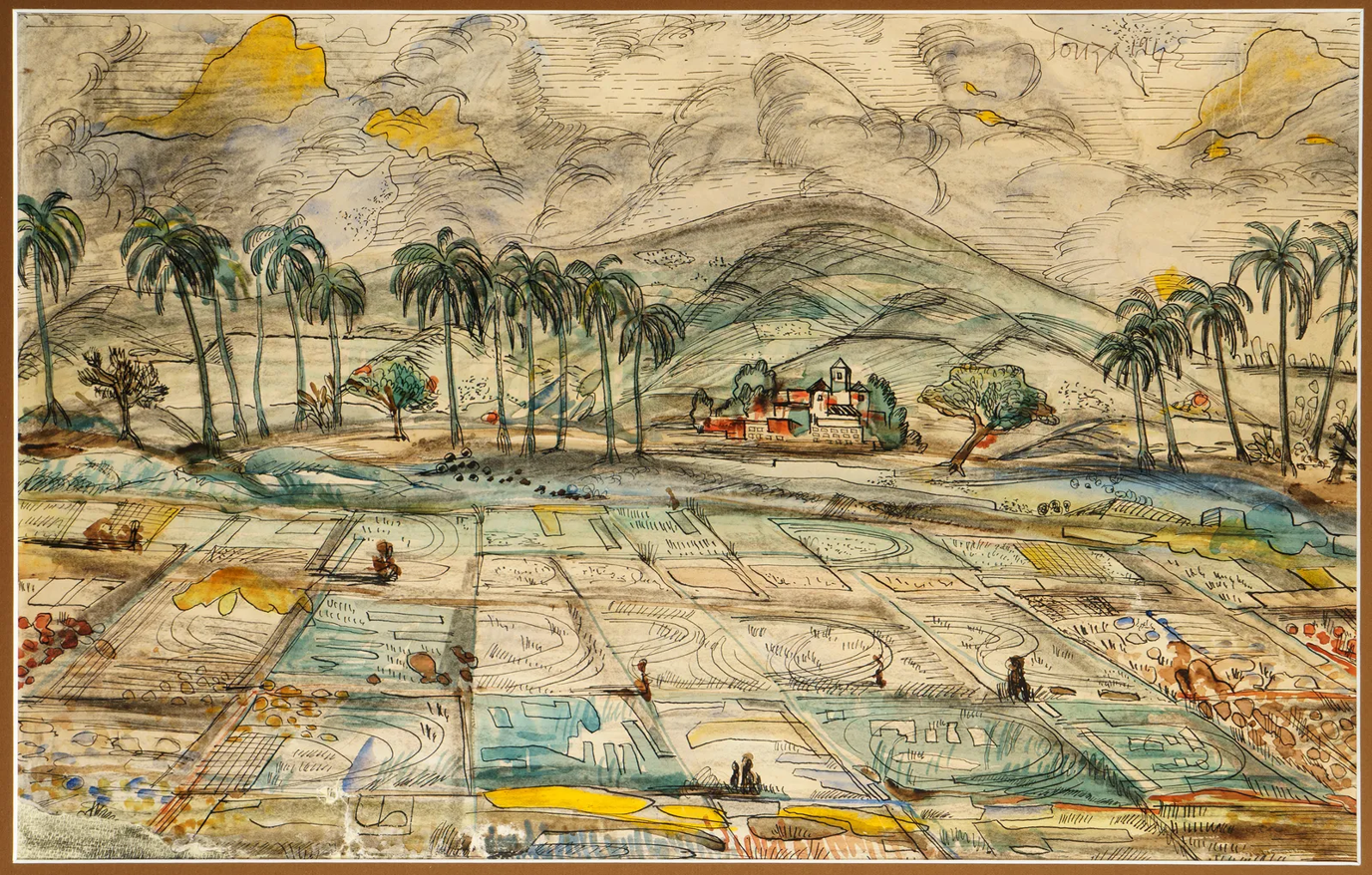

The khazans were sustainable ecosystem agrarian modules that operated on tidal, hydro and solar energy. The system integrated agriculture, aquaculture and salt panning. They were practised on reclaimed coastal wetlands, mangrove areas and salt marshes. This system was designed to be sensitive to indigenous biodiversity. (Sonak, 2014). The surplus from these harvests was enjoyed by the gaunkars of the Comunidades. The Khazans faced a major blow when the people began fleeing to Novas Conquistas. With no one to take care of the bunds, the land became infertile with the growth of weeds and jungle wood. The decline in agricultural produce meant a decline in commerce. Commercial establishments were shut down and economic life was paralysed since the taxes were no longer paid. With increasing expenses the Portuguese were obliged to put an end to religious persecution and call back the refugees. Once the villagers returned the Comunidade lands were back in their former glory and the commerce prospered and the ecosystem was restored. Today Khazan lands are again facing a major blow due to tourism and urbanism. These Agro-ecosystems are constantly transforming to cater to the tourism industry and this is predominantly visible in the Coastal areas. There has been an increase in land values along the coast. “Hills which were earlier green and untouched, have today become closely coveted by realtors and land speculators. Fishing and agricultural-based villages are turned into concrete jungles” (Noronha, 1999).

The tourism sector has hardly benefited 10 % of Goans (Noronha, 1999) who are either small-scale entrepreneurs or large corporates. Hinterlands are at an increased risk of being exposed to tourism-based activities as well. The rest is enjoyed by international companies who purchase lands to construct hotels, resorts etc. There is a constant battle against the degradation of the coastline due to a lack of long-term planning. Even though the state government has sufficient power, it fails to implement sustainable and eco-friendly development measures. Corruption and misappropriation are evident in the real estate market. Village panchayats have failed to regulate these activities. Building regulations are being violated and locals are in a constant battle to protect their environment. There have been numerous protests and strong anti-tourism activism widespread today.

Traditionally, the gaunkars were legally qualified to take delivery of the ordinary and extraordinary works related to the villages. The gaunkars also had the exclusive right to execute these works. The profit from the lease of fields and other properties was quite substantial because they were sub-leased. The Gaunkars also shared their surplus with their Kullacharis when they provided their service. After the Portuguese rule, a new set of members who were non-residents became a part of the community by purchasing the right to share in the annual surplus. They were known as Khuntkars. They were only allowed to have a share of the surplus and not the privileges of the gaunkars i.e “ the right of voto - e voz - the right of management and the right to bid in the lease-auction of the properties and that of the works to be carried out” (Periera 1978).

From the 1970s, the government-sponsored land reforms and the Comunidades lost most of their control over the paddy and cashew cultivation which were the two important agricultural assets in the Old Conquest. (Axelrod 1998). From being auctioned triennially to the highest bidder, the Comunidade lands were auctioned by a 25-year and then later a 99-year lease. This in a way made the bidder a permanent owner which has, in turn, affected rural development. The legal structure overrides the tradition where one would pay for and have access to use the land. The owners today no longer pay taxes. Along with the intervention of the panchayath and the new regulations the Comunidades fail to perform the duties they were previously obliged to. (D’Cruz, 2005) “After liberation, many dominant gaunkars immigrated. But, even they enjoy the zones is absentia. Many outsiders came to settle down in the villages.” (Gomes, 1996). The change in land use, land cover, property rights, and politics along with population movement affects the relationship between people and the ecosystem. Goans are being excluded from the opportunity to make decisions for their environment and economy affecting not only their lives but of the environment.

Today agriculture is no longer the main source of income and is performed by a few. Conventionally, the gaunkars valued their organic and historical relationship with the land and its resources. Today it's no longer the same. Tourism and Urbanisation have led to economic development and diversification. But along the way, Goa is losing its identity. What started as an agrarian society with a deep understanding of nature, has turned its back on environmental issues and is focused on an inherently unstainable route toward tourism and economic development. There is a need to understand the issues of land use, planning, and community participation in policy-making for tourism. There is a need for sustainable tourism development which best suits goa and does not change the identity of Goa. The Comunidade system provided an opportunity for the community to take care of its ecosystem while reaping its benefits. It integrates the locals in the decision-making for its environment.

Bibliography

(1) https://geoportal.natmo.gov.in/search/field_topic/goa-532

(2) https://www.architecturaldigest.in/content/goa-francis-newton-souza-art-exhibition/

(3) https://geoportal.natmo.gov.in/search/field_topic/goa-532

(4) (Jacob, 2019)

Axelrod, Paul, and Michelle A. Fuerch. “Portuguese Orientalism and the Making of the Village Communities of Goa.” Ethnohistory 45, no. 3 (1998): 439–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/483320.

Pereira,Rui Gomes “Gaukaria the old village association”. A. Gomes Pereira. 1978

Sharon D’Cruz, and Avinash V. Raikar. “Democratic Management of Common Property in Goa: From ‘Gaonkarias’ and ‘Comunidades’ to Gram Sabhas.” Economic and Political Weekly 41, no. 5 (2006): 439–45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4417767.

J.F. Gomes, Olivinho. “Village Goa: A Study of Goan Social Structure and Change”

S.Chand (G/L) & Company Ltd; 2nd edition (1 October 1996)