While Dharavi remains under threat of callous high-rise redevelopment, the unrecognised incremental efforts of skilled local artisans should be understood as an essential source of knowledge

Activities of construction often spill out from institutionalised professional boundaries. Metropolitan architectural projects, urban infrastructure and real-estate developments rely on the large-scale mobilisation of capital, usually sourced in speculative financial markets. Yet a majority of the world’s inhabitants raise small amounts of capital from their community networks to finance a local economy of incrementally growing construction projects, building houses, shops and even infrastructure. Such incremental processes have always been at work, and have been instrumental in the development of habitats, not only in villages, but in some of the largest cities in the world including Mumbai, São Paulo, Seoul and Tokyo.

‘In our years of collaboration with local builders in Mumbai, we have witnessed that their work expresses a contextualised intelligence and a resourcefulness born out of adversity’

Local skills and resources fuel construction practices in neighbourhoods that fall outside the planned regimes of urban habitats. Self-organised masons, labourers and artisans produce habitats, and transmit skills and knowledge to the next generation of local builders. The result is a planetary vernacular urbanism that is systematically overlooked or dismissed as ‘informal’, the adjective evoking something that lacks form, that is messy, confused and irrational and should be replaced with something neat and orderly. Rather than informal, we call these habitats ‘homegrown’, a term that expresses the capacity of a settlement to develop from within.

About half of Mumbai’s 20 million inhabitants live in settlements categorised as slums by the government. Due to the contested state of their occupancy rights, their houses are deemed illegal and are under constant threat of destruction. They are also systematically denied basic infrastructure on the grounds that they should be redeveloped rather than upgraded, despite the fact that a huge proportion of ‘slum dwellers’ have lived there for generations and provide essential services to the city as municipal workers, drivers, restaurant staff, construction workers, policemen, office clerks and business owners.

Dharavi is a massive settlement at the heart of Mumbai, infamously (and wrongly) described as Asia’s largest slum. Over the years, local builders, in Dharavi and similar neighbourhoods, have been engaged in the process of building homes, improving local civic infrastructure and servicing the housing needs of millions of the city’s residents. These builders are typically hired by families keen to rebuild their home, selected on the basis of their previous work and common acquaintances. Contractor and client live in close proximity to each other and often belong to the same community. They discuss what should be done, agree on a schedule and budget, and the work starts. No formal plans or contracts are signed. Trust and reputation are everything. This process is not unique to Dharavi, Mumbai or India. This is the way artisans have been working with their clients since the dawn of time.

Our practice, established in Mumbai 12 years ago, aims to recognise and honour the role of these local actors, who are often blamed by civic authorities for operating illegally, in the production of their own habitats. To us they are the anonymous heroes of an epic story of building neighbourhoods out of nothing, transforming meagre local resources into functional mixed-use habitats. Over the past 10 years, we have collaborated extensively with inhabitants and artisans on the design and construction of many small homes in Dharavi, where our office is located. In 2016 we initiated The Design Comes As We Build project to reveal the hidden logic in the way Dharavi houses are built, and turn the faceless artisans of construction into designers and model makers – in effect turning a building type often dismissed as ‘informal’ into a form that is not only perfectly rational, but also beautiful in its simplicity and ingenuity.

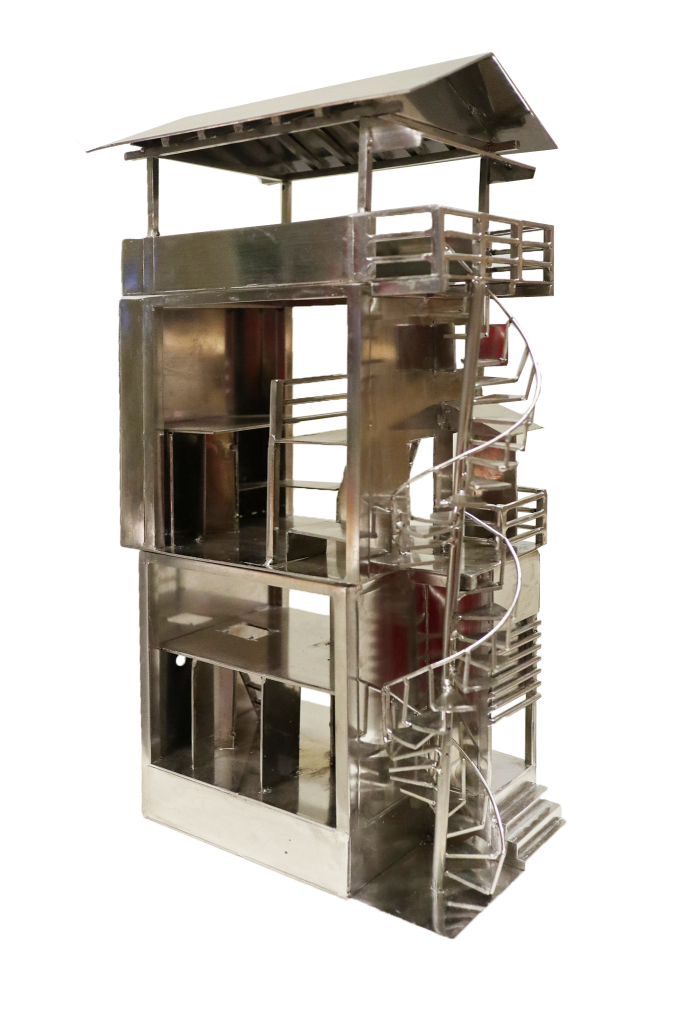

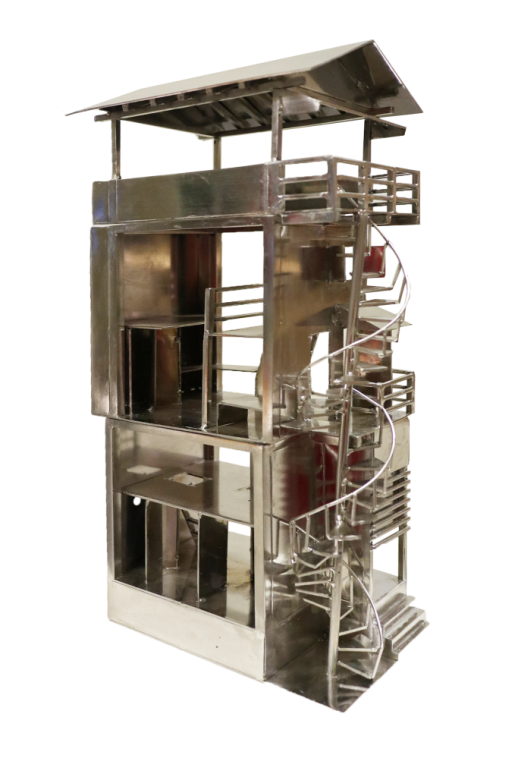

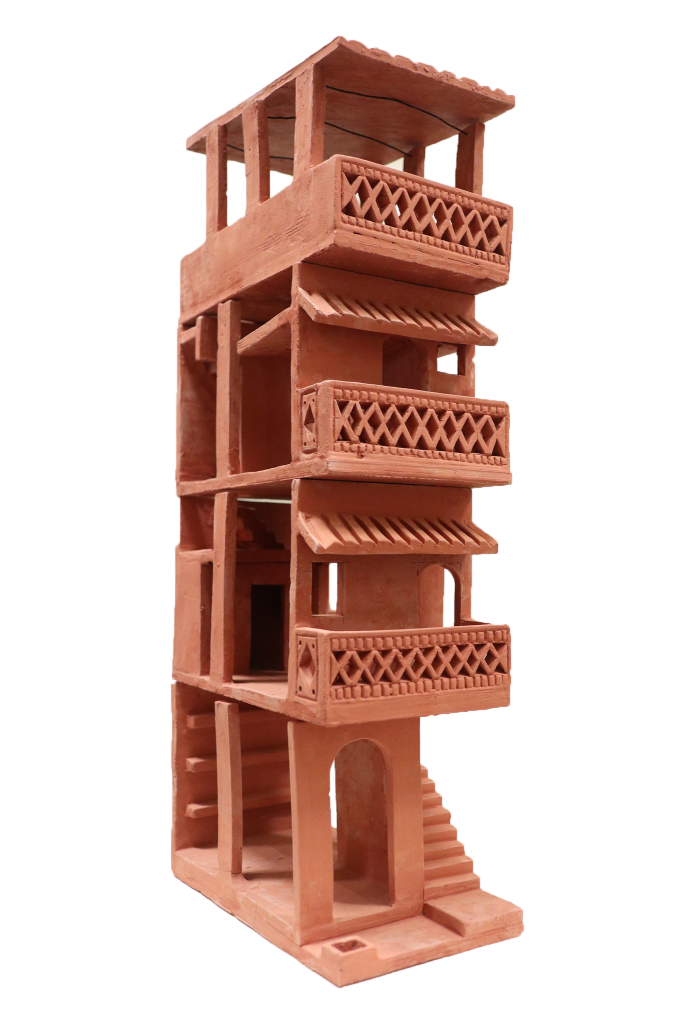

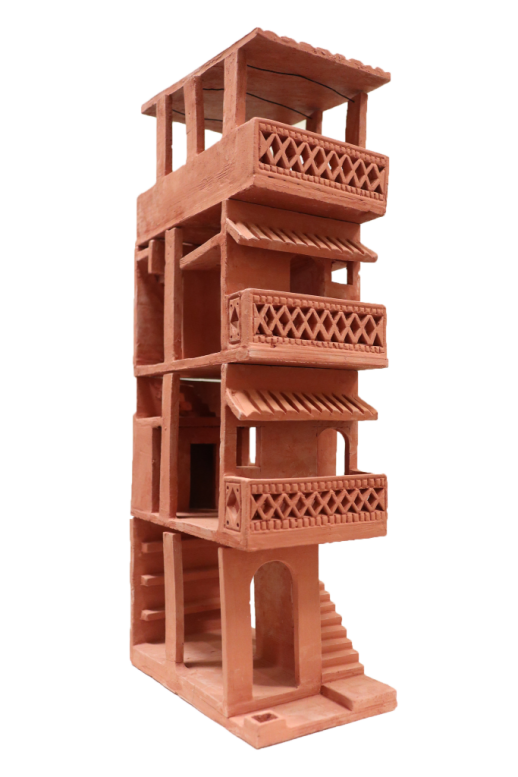

Models built by skilled labourers in Dharavi out of the materials they specialise in: steel, clay, wood, glass and recycled plastic

To translate the practical expertise of local builders into ‘designs’ that architects could relate to, our team asked several builders from the neighbourhood to think of the best possible design for a typical Dharavi house of 12 x 15ft, which should also accommodate some form of economic activity, as most households use their house as a tool of production. We call such live-work units ‘tool-houses’, a building type that corresponds to the needs of a large segment of the population.

We turned these visions into 3D drawings. We did not intervene in their designs, but encouraged them to be ambitious to think of the best possible small house for Dharavi. Some of them described new ways of optimising space and the use of materials, using spiral staircases, creating semi-open spaces on the rooftop for social gatherings, or making provisions for the future growth of the family. Others imagined multiple ways in which the house could be used to generate income, providing space not only for retail on the ground floor, but also rental units that could function independently from the rest of the house. Some projects include innovative systems to protect from sunlight or ventilate the house.

‘To us they are the anonymous heroes of an epic story of building neighbourhoods out of nothing, transforming meagre local resources into functional mixed-use habitats’

Once the drawings were done, we asked the artisans to build models using the materials they specialise in: steel, clay, wood, glass and recycled plastic. The builders and the craftsmen sat together and modified the design as it took form. The result is a series of models, videos and photos that tell a story of how people manage to create habitats that are full of life, even in the most difficult conditions.

For the past three decades at least, the municipal authorities have been constantly planning and failing to ‘redevelop’ Dharavi. The plan is to turn this vibrant low-rise, high-density neighbourhood, where hundreds of thousands of people live and work, into high-rise mass housing, with tiny units of 200 to 300 sq ft intended for families that rarely have fewer than seven members. The government’s plan faces strong opposition from the inhabitants and others who, like us, believe that more will be lost than gained in the erasure of the complex, mixed-use typologies that characterise the neighbourhood. Today the government privileges a piecemeal implementation of the plan in which real-estate speculation – thanks to the metro station currently under construction in Dharavi – will see its definite transformation into high-rise units, pushing millions of worker-residents away.

Urbz asked some of the many skilled labourers, who have worked in Dharavi for years, to imagine idealised homes for the area

In our years of collaboration with local builders in Mumbai, we have witnessed that their work expresses a contextualised intelligence and a resourcefulness born out of adversity. Ignoring their contribution to the city’s urban development is a recipe for failure. This failure is not theoretical – it can be seen all over the city wherever a ‘slum’ has been cleared up and replaced by rehab housing blocks. Built in haste, with poor design and even poorer materials, these soon become dysfunctional and – unlike the so-called slums they replaced – they are impossible to upgrade. ‘Slum-dwellers’ seem to leave rehab buildings shortly after being resettled, having lost their connection to the neighbourhood, which is not just a place to live, but also a space of intense economic and social activity.

The first series of models from The Design Comes As We Build were first exhibited at our office in Dharavi and then at the Bhau Daji Lad Museum, Mumbai’s city museum. These local builders, referred to as ‘contractors’ in Mumbai, are usually portrayed by the media, the public administration and by professional architects as unreliable at best and crooks at worst. Our intention was to show their contribution to the city and the potential they represent for Mumbai. It is this active legacy that we wish to recognise and value, as we believe that it is the key to improving the living condition of the 60 per cent of Mumbaikars who live in so-called slums, and should be integrated into the government’s strategy for the development of Dharavi. The models have since been exhibited at the MAXXI Museum in Rome, at an Arc en Rêve exhibition in Lille, and three of them were acquired by the M+ Museum in Hong Kong for its Asian design collection. We realised that, with the sale of one model, we could almost build an actual house in Dharavi. This prompted us to initiate a new phase of the project called Homegrown Street, where we will attempt to finance the upgrading of an entire street by selling models of each house.

Dharavi is at once extraordinary because of its sheer size and density, and ordinary because it reflects a prevalent urban condition, which will likely grow in importance throughout the 2020s. When global capital stops speculating, when state bureaucracies fail to ‘modernise’ our infrastructure (or simply maintain it), when architects find themselves out of jobs, what we are left with are homegrown neighbourhoods, which reclaim growth at their scale – locally, incrementally and spontaneously. Ignoring or dismissing these dynamics at a time when they are our cities’ most precious assets, is both foolish and criminal.