‘Our lives are 50-50’

‘Our lives are 50-50’

The second Sunday of every month sees an unusual gathering at Five Gardens in Wadala, Mumbai. Small groups coalesce into circles looking as if they are about to share a picnic lunch. Instead, they bring out logbooks, attendance registers, receipts and vouchers. One group discusses a plan for a water supply system. Another makes a budget for a festival. A third presents a case for a student in need of a scholarship. As BEST buses thunder past and local residents wander around the park, few can guess what these groups are up to.

They probably don’t imagine that each of the people sitting there, Mumbaikars to boot—with roots in the city going back decades, sometimes generations—have one part of their lives, minds and hearts firmly wired to their ancestral villages. Families and clans with one foot in the village and the other in the city have done more to urbanise the 70% of India that is still officially rural, than any rural development scheme. They are responsible for a quiet construction boom all over the country. Urban-style homes, temples and mosques are being built with remittances from cities. Sometimes money also comes for infrastructure improvement, schools, or investment in the local economy.

Like millions of Indians all over the country, those discussing their village affairs in Wadala are rooted in more than one place. For many, moving to the city has not meant a relinquishing of ties to the village. From a third generation resident in Matunga with live connections to Tirunelveli in Tamil Nadu, to the bus-conductor or taxi-driver you encounter in any part of the city, many urban dwellers lead dual lives. As a traveller to Ratnagiri town once informed us on the Konkan-Kanya express, heading home during Ganpati, “We belong to both places, our lives are ‘50-50’”.

Ratnagiri on their minds

This dual affiliation is nothing new. It is part of an old pattern of migration in India. Historian Sanjay Subramanian describes in detail circulatory movements that have shaped the sub-continent’s labour landscape for centuries. Raj Chandavarkar, chronicler of industrial Mumbai, speaks about how much the district of Ratnagiri remained part of workers lives, helping them through strikes and labour struggles as they contributed to make this megapolis genuinely modern.

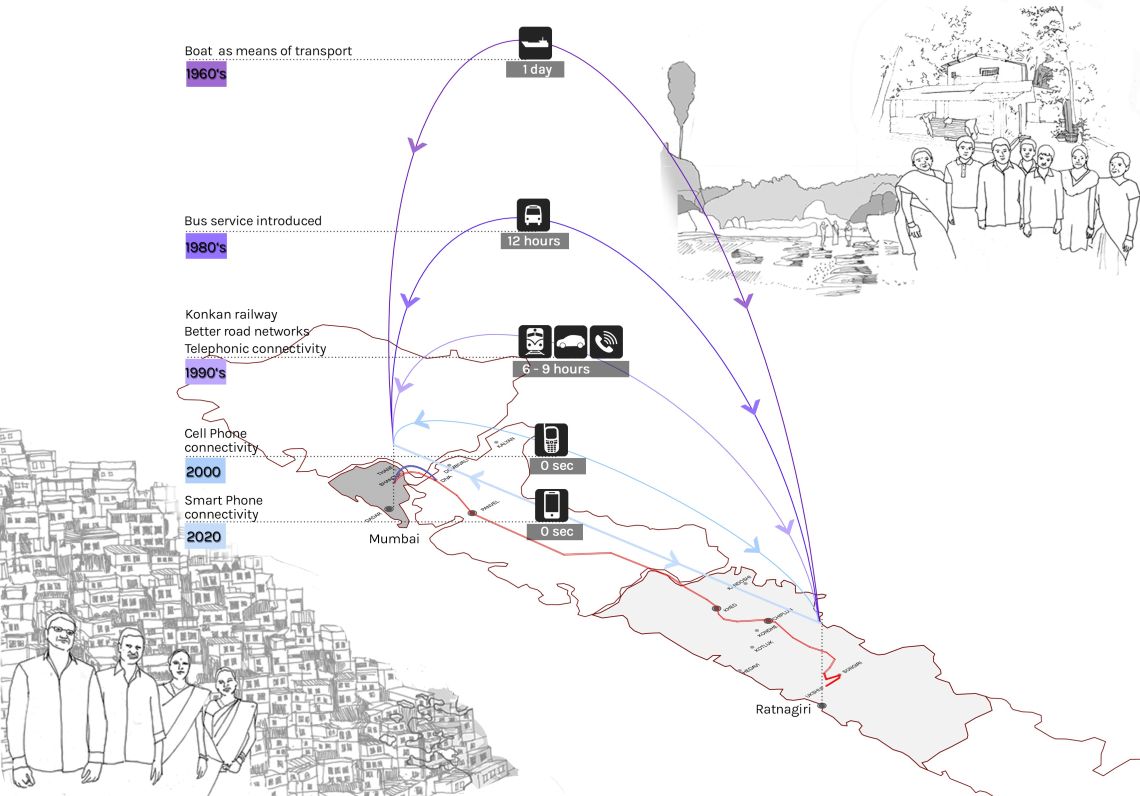

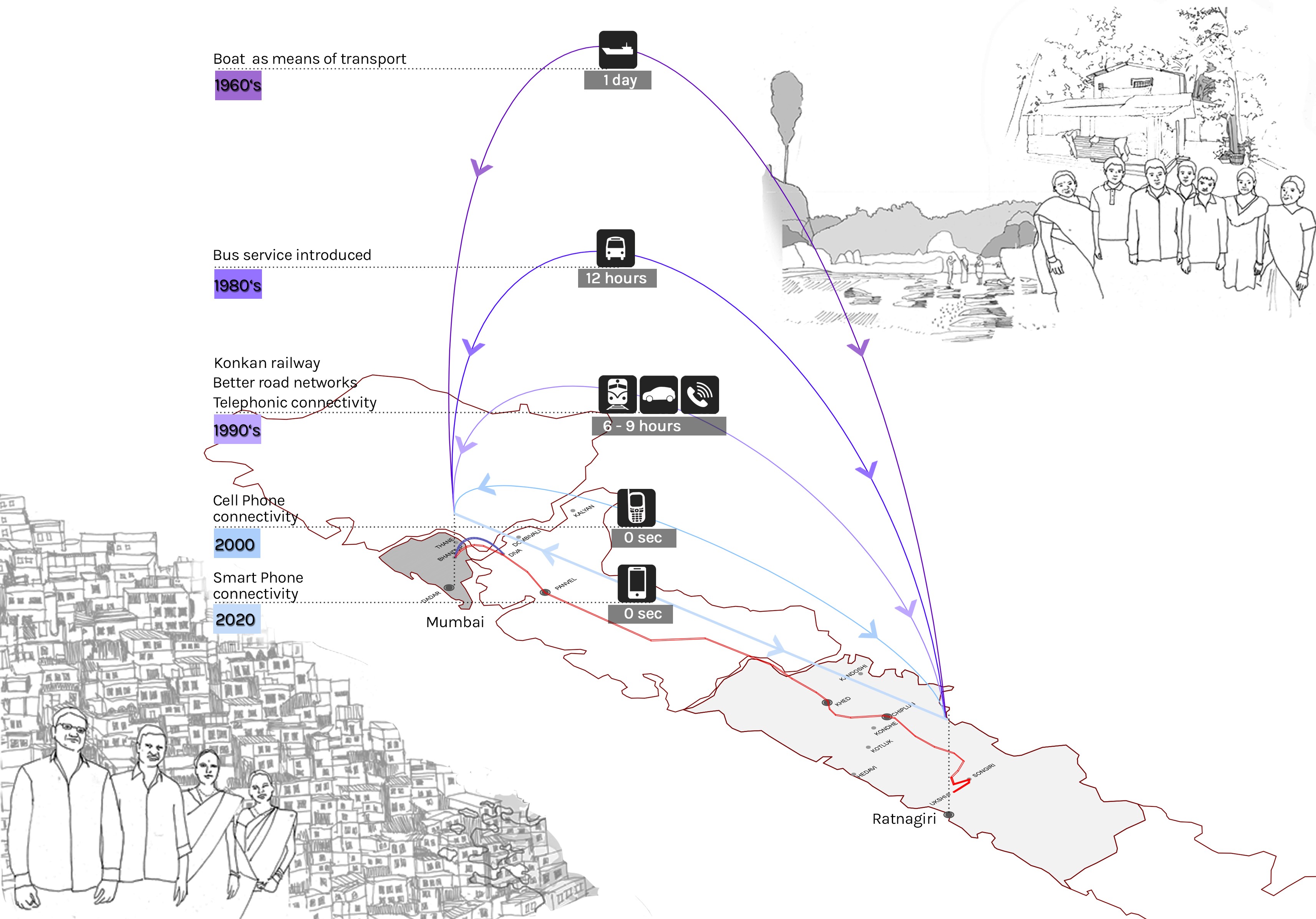

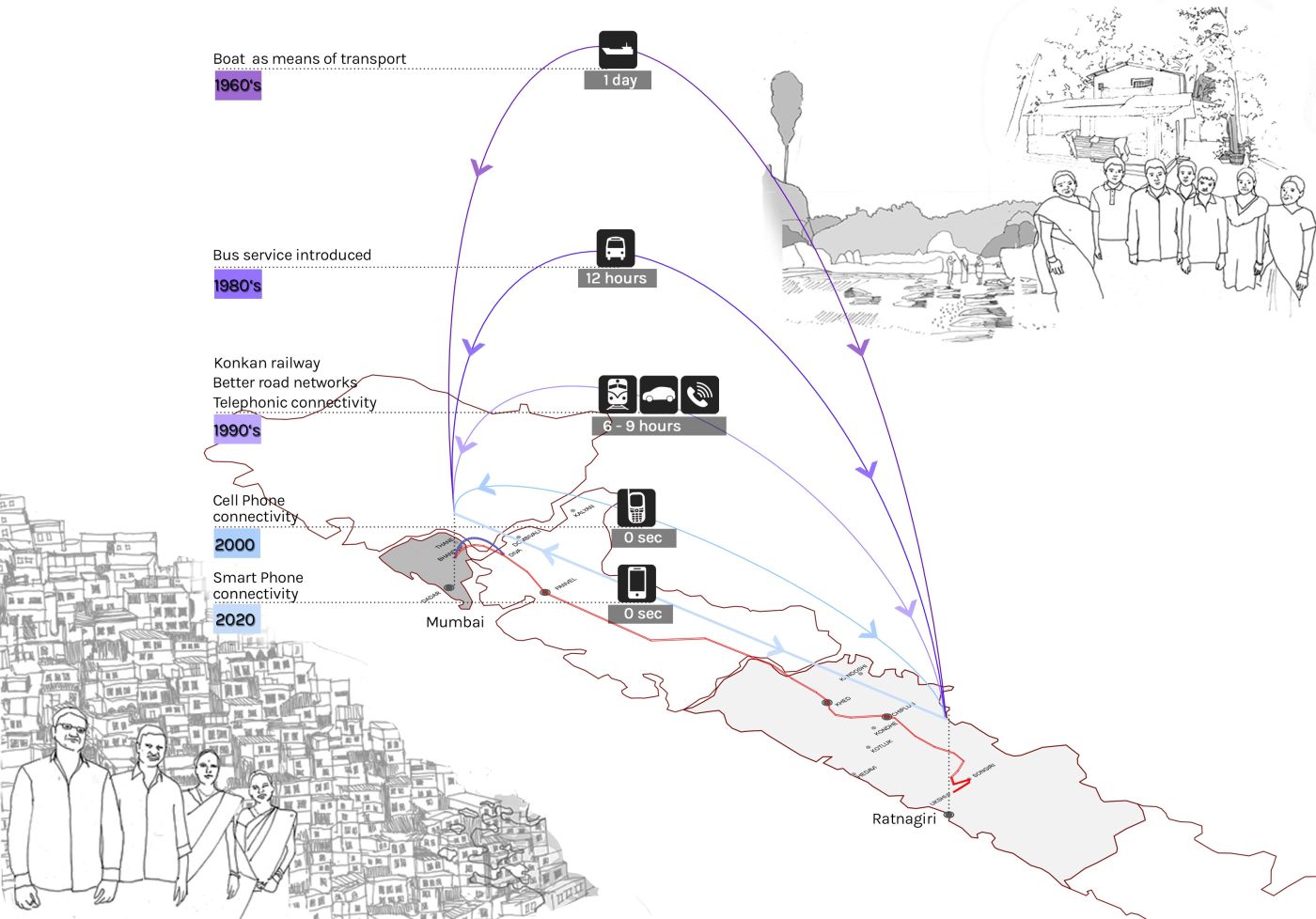

Even today, many residents in the old mill areas of the city and in large ‘homegrown’ pockets of Mumbai such as Bhandup, have Ratnagiri on their minds, and in their lives. They travel annually at the minimum and more often whenever they can. They keep in touch via relatives and neighbours. They send money and monitor how it is being used. They stay connected via mobiles and smart phones whenever the network allows it.

India’s extensive railway network is the infrastructural backbone of this circulatory urbanisation. Family, clan and community are its cultural lifeblood. Users of the Konkan railway we interviewed mentioned family visits, attending festivals and pilgrimages as the prime reason for their journeys. The idea that migration to the city is not a one-way street, but actually a loop with movements going back and forth from rural to urban, is slowly starting to make its way among researchers and policy-makers. This phenomenon is hard to capture statistically yet it has vital implications for urban planning and policy-making.

Lowering the drawbridge

What urban India needs is a genuine lowering of barriers of entry into cities—without it becoming a site for political opportunism and vote-banks. It needs to widen its scope and not treat migration as a burden. This approach goes beyond poorer migrants and slum dwellers to include people across classes and groups—from single women trying to make it in the city, strugglers in various service industries, first-time entrepreneurs and fresh graduates. For instance, planners could address the need of temporary rental accommodation, where people can stay for a few years, till they move on, move back or get the means to move to a permanent place. While governments and developers focus exclusively on providing permanent housing for nuclear families, new forms of habitats and accommodation keep emerging in slums to respond to an enormous, yet unacknowledged demand. It is time that our policies start reflecting India’s fluid and looped urbanism more accurately.

The article was first published here as a part of the fortnightly column 'Place, Work, Folk' for The Hindu Sunday Magazine.