Water system in Dharavi

Water system in Dharavi

19.0402084, 72.8508504

Dharavi, Mumbai

Dharavi, a very dense, self-built settlement located at the heart of Greater Mumbai, has developed its own infrastructure over time. The system, built incrementally by local plumbers and residents is a complex one. Urban planners and architects typically dismiss locally built infrastructure and instead advocate the redevelopment of the entire area.

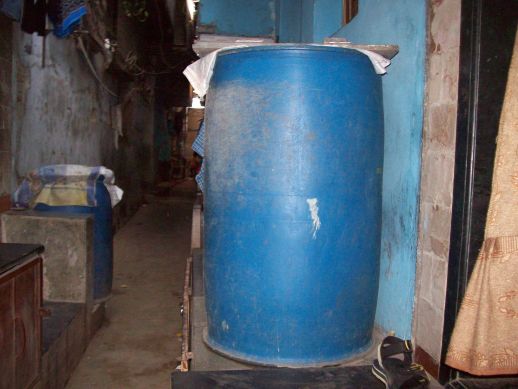

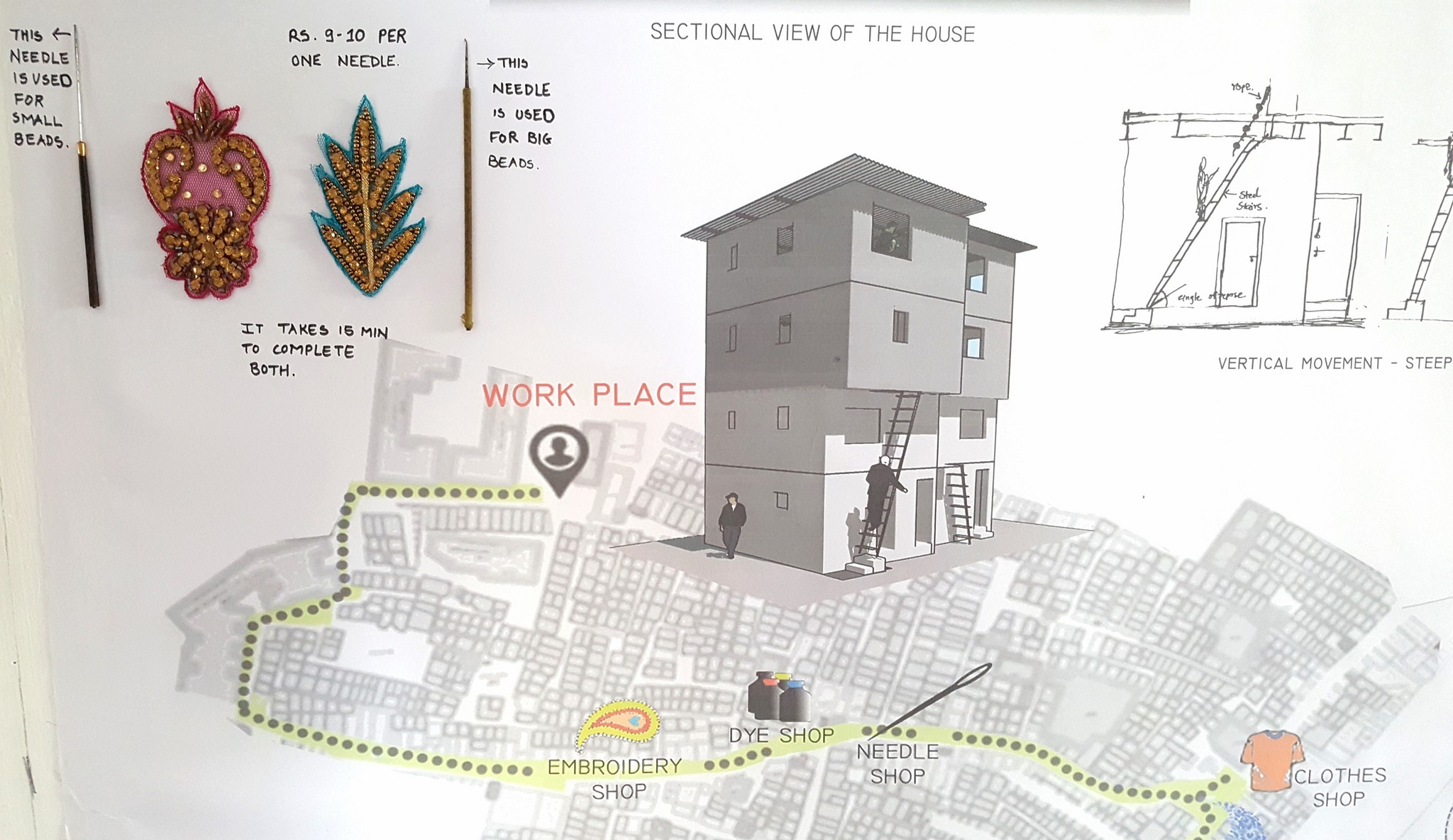

Together with Shyam (Dharavi Resident and URBZ researcher), we explored the water systems in Dharavi. As we walked along the lanes of Dharavi, we encountered several pipes on the ground surface. Small pipes branch out of bigger pipes, while other pipes carry sewage water. Not every house in Dharavi has direct access to fresh water. But most have pipes hanging outside. The longer the roll of pipe, the further is the fresh water tap from the house. Along the lines, we also observed open drains that simultaneously carry sewage and storm water. These sewage drains are sometimes contaminated by pollutants from small industries and are typically filled up by insoluble things like plastic articles.

Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC)

It takes five houses to come together to get a connection for water from the BMC. Each house ends up selling around 3500 Rupees for this kind of shared connection. When a legal water connection is established, BMC workers make sure that openings for few additional connections are made but not given to anyone. If one needs access to these spare connections, which are not officially accounted for by the BMC, they have to bribe BMC officers. Such connections typically cost 5000 Rupees each.

Availability of Water

The water is released by BMC in the mornings for approximately 2 hours at varying times in different areas. The pressure of water depends upon the proximity of the house to the main water pipe. When several small pipes are connected to one big pipe, the person staying closest to the big pipe receives water at a high pressure. At times no water is released. This uncertainty is a great stress factor for the residents. And in such instances, either the resident takes help from the neighbours or has to buy water from stores or the tankers thus incurring an extra expense.

Quality of Water

The fresh water pipes bring in murky water initially so the residents need to let it go and wait for clean water in order to store it for cleaning and drinking purposes. Most residents filter the water using a fine fabric and boil the water for drinking purpose. For some residents boiling water is an extra expense that they cannot afford.

It is very interesting to study the intricate water system in the user generated habitat of Dharavi. The complex network of pipes is legible to the residents and local plumbers alone. They are the only ones who can recognize their particular water connection pipe. There is always a sense of insecurity among the residents of Dharavi as they do all they can to ensure that their connection is safe and the water available. Houses that have no connection rely on their neighbors. The people of Dharavi have been very innovative in working with the water system and have succeeded in improving their conditions. There were times when people had to form queues early in the morning for water. And not everybody would make it to the tap before the water stopped. Till about a generation ago, wells were present in many parts of Dharavi. Only a handful wells can be found in Dharavi today. The availability of piped water and the lack of space has made them defunct.

A more cooperative attitude of the BMC would definitely help to improve the infrastructure. A very large number of houses have not received their water bills for several years. Many households have suddenly been asked to pay huge amounts of money (accumulated water bills) to sustain their water connection. The way people have adapted to a dysfunctional system is inspiring and can teach planners and architects a great deal. The ability of Dharavi residents to streamline available resources in the most efficient way is extremely impressive.

This article summarizes preliminary research by Sameera Rao, a graduate student in Landscape Architecture at Ball State University and intern with URBZ, July-August 2011.