The city: Integration vs Segregation

The city: Integration vs Segregation

The clash between the mainstream image of the contemporary megalopolis made of shining high-rises and the lesser acknowledged spatial reality of many, if not most, of its inhabitants, is not occurring only in Mumbai. Rather, it is a common feature of many cities around the world.

What may look like an aesthetic or economic contrast only, may hide a crucial issue for today’s cities; the relation between urban space and the individual engaging in it or producing it.

In fact, it is important to clearly understand that elements of contemporary urban life are determined by how urban space is produced, by whom and for what reason.

Billboards advertising brand new real estate housing complexes promise a comfortable and affordable dream-life, in a safe and ordered environment. For sure this lifestyle, or urban morphology, suits a certain kind of modern urbanite, but on a larger scale, such spatial arrangements may eventually weaken other positive urban features.

In fact, cities can be at the same time a device of social and cultural integration or a device of separation and marginalization. The tendency towards one of the two extremes is related to the physical characteristics, the functions and the uses that urban space assumes or the activities which happen on it. However, all of these are connected ultimately to the opportunities that citizens actually have to engage with it.

A greater presence of inclusive and open urban environments, which are able to offer opportunities for mutual awareness, learning and cohesion, favours the role of the city as an integration device.

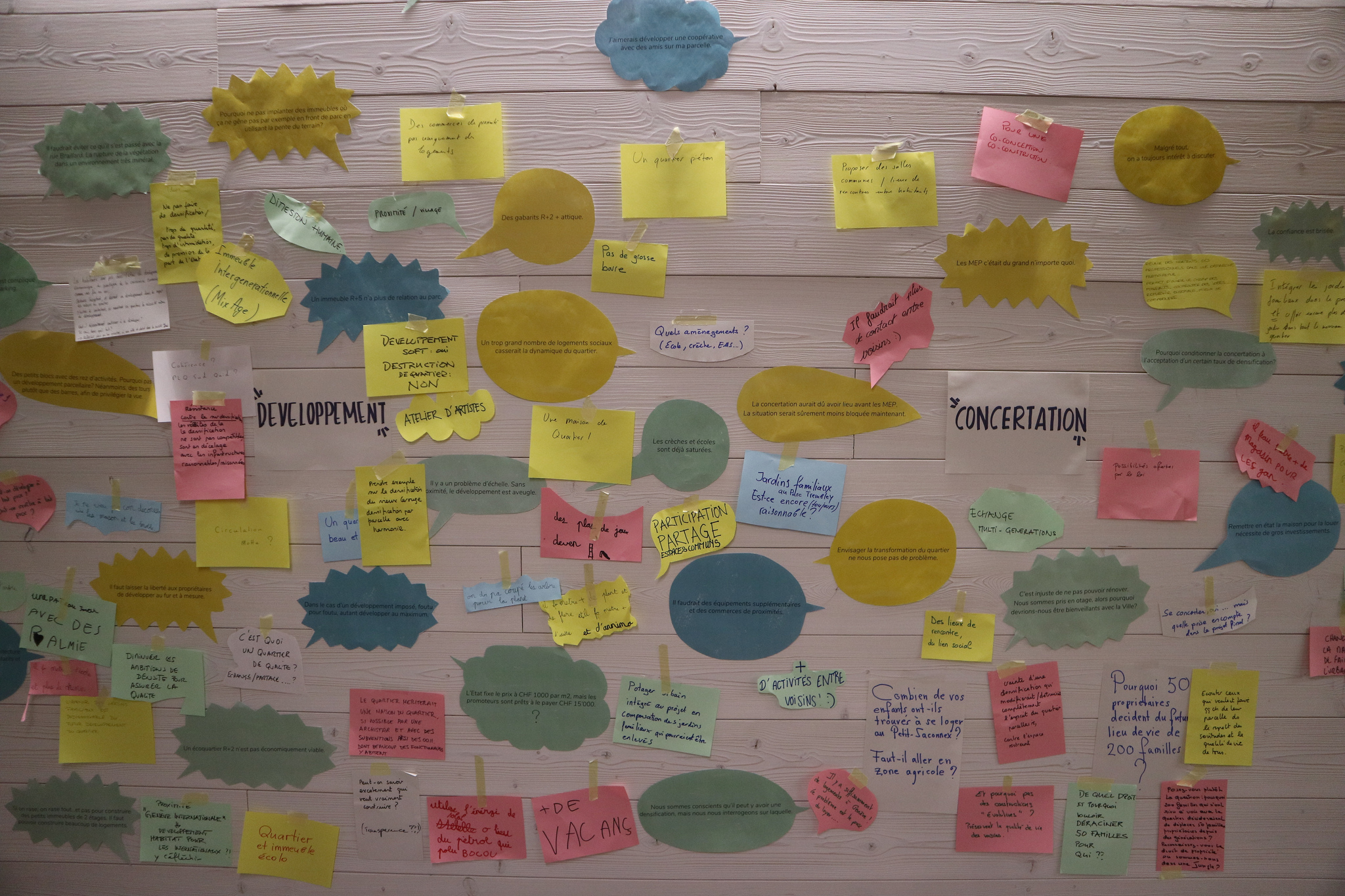

At the same time, shaping a city as an integration device is not an easy job. Since they are spontaneous and personal acts, relations between citizens cannot be planned or forced: at best, an urban space with some physical features capable of hosting or fostering them can be built.

Such challenges are often ignored by real estate urban plans: they mainly follow an ideal of a highly zoned urban space. Which means that, at a larger scale, such an approach can give rise to a fragmentation of the city into many mono-functional sub-parts, frequented by a particular user, fuelled by purchasing power.

The primary goal of real estate urban interventions, from a common economic perspective, is earning profits and covering investments. Which means that interventions that solely and relentlessly follow a logic of commodification of urban space inevitably push the city away from its integrating role, transforming it instead into an urban landscape that is highly separated, in which some parts of the city are accessible to only those who can afford it.

On the other hand, the urban spaces such as homegrown settlements or older neighbourhoods with complex occupancy and ownership arrangements, despite their countless problems, may succeed in shaping urban environments in integrative ways.

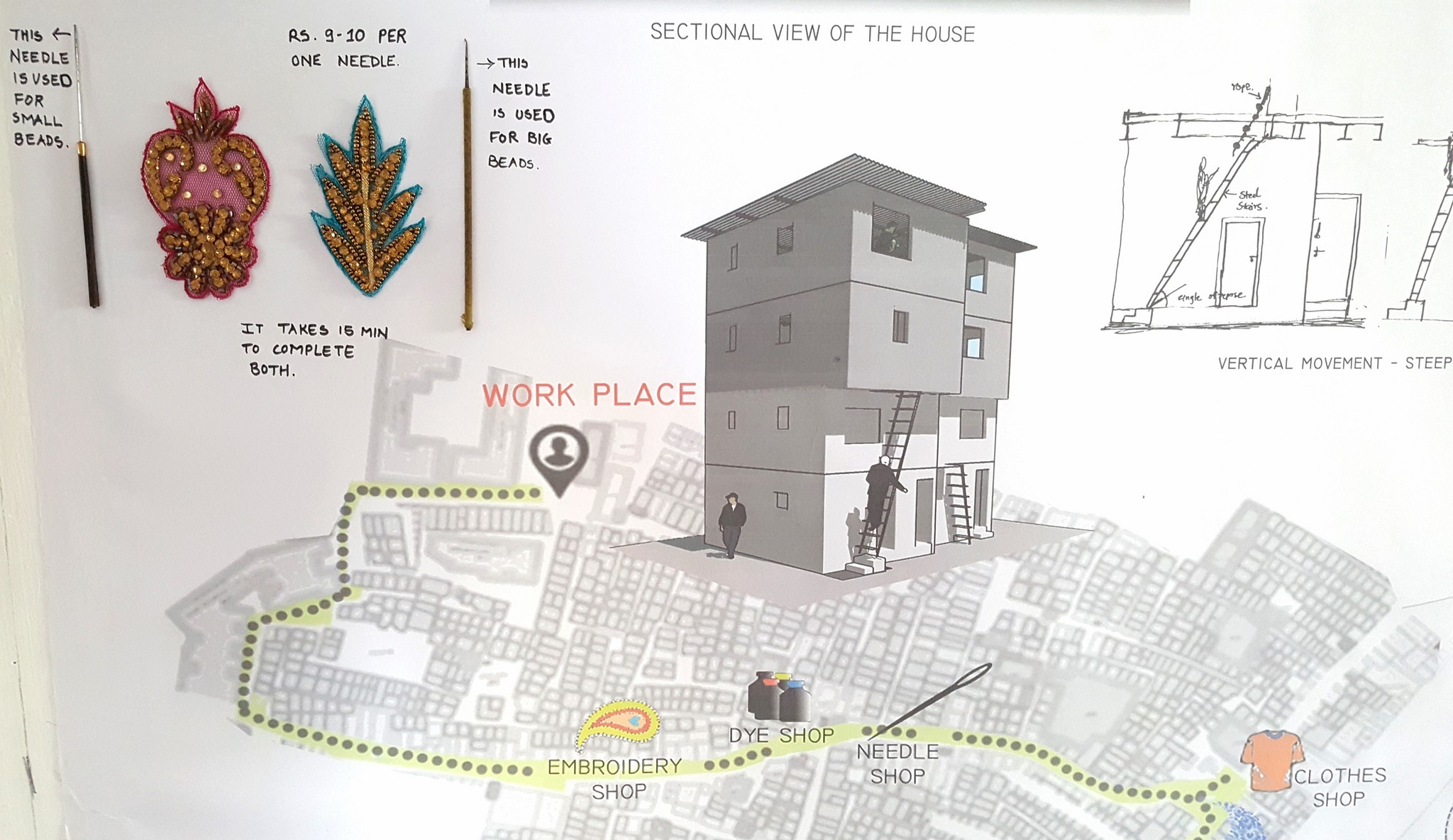

urbz demonstrates that Dharavi is a prime example of the positive urban feature that an user-generated neighbourhood can produce: a dense mix of uses, relations and interconnected functions that give rise to a highly productive and multicultural community.

The key to achieve such positive features is the close relationship between inhabitants and urban space. The same challenging circumstances that forced people to provide themselves with housing solutions facilitates very diverse communities to share limited spatial resources.

Consequently, engaging with spatial issues has led people to become wise mediators, negotiators, smart at spotting possible compromises or implementing mutually beneficial, spatial configurations.

Unlike the ordinary urban planning paradigm, such settlements generally and progressively evolve by carefully measured micro-planning events carried out by many individuals who act in a context where they are aware of actual possibilities, probable conflicts and, above all, the moral imperative of not wasting precious space.

Local praxis is adaptive and determined by the individuals’ reactions at the constant change of circumstances and actors involved at all scales and spheres, supplying site-specific solutions deeply rooted in the local context. Through these circumstances, Dharavi developed as a highly integrative urban device, capable of flexibly providing accommodation and employment possibilities to many.

In terms of urban environment, the differences that inhabitants have in the levels of accessibility, flexibility, and self-determination over space produces a spectrum of different arrangements.

Real estate development on the hand, has a functionalist approach towards planning decisions, treating space as a neutral, passive element, turning spatial relations into speculative projections and removing its productive capacities. Flexibility or adaptability is explicitly discouraged in this context.

The highly fragmented structure of Mumbai, where homegrown settlements and historic chawls are widely spread in all parts of the city as much as new high-rise, investment-driven units, we see the city producing a melting pot of citizens from different backgrounds. Despite living in very different housing typologies they are always at a short distance from one another. This feature is fundamental to keep alive the role of the integration device that the city already performs.