Gendered Mobility and Climate Action

Gendered Mobility and Climate Action

This blog is an introduction to the research project undertaken under the C40 Women For Climate mentorship program, Mumbai in collaboration with the Government of Maharashtra. The Mentee, Vidisha Dhar, is supported by Lubaina Rangwala (WRI), urbz collective and Anamika Sarker, a student of built environment at the Jindal School of Art and Architecture.

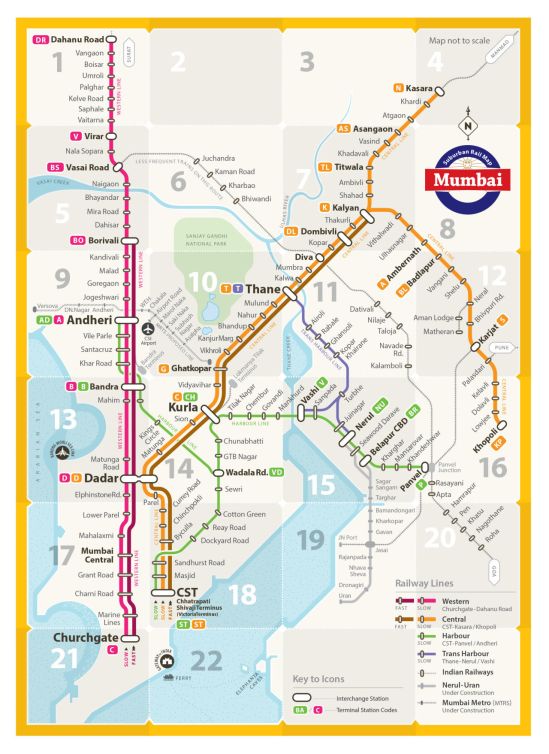

The city of Mumbai is synonymous with images of roads congested with cars, buses, auto-rickshaws and kali-peelis (the local black and yellow cabs). Thankfully for the city, there is also the provision of a robust suburban rail network system that runs 2,342 train services and carries more than 7.5 million commuters each day1, ensuring that the Indian metropolis that never sleeps also never comes to a stop. The suburban rail network, along with the other modes of available transport, makes public transportation in Mumbai well-connected, accessible and affordable to commuters across socio-economic strata2.

Recent studies have established and demonstrated the transport industry's significant role in climate change. According to the United Nations Interagency Report from the Second Global Sustainable Transport Conference in 2021, the transport sector produces a quarter of all energy-related emissions, which is expected to increase unless no significant measures are taken.3 Public transport becomes a strategic entry point in the systemic transformation required to combat the current climate crisis. The previous mobility plans for Mumbai have only addressed the quantitative aspects of mobility, using numbers to represent people.4 This fails to recognise the diverse experiences shaped by people's lived realities. When tackling the issue, people who commute in the city must not be neutral citizens, i.e., their identities and subjectivities should be accounted for to ensure an inclusive public transport system. Various factors affect travel, ranging from gender, marital status, economic class, occupation, domestic responsibilities, etc. These have effects on the choices that people make, what mode of transport they use (or are compelled to use), what time they commute during, where they live, whether they travel alone, with dependents or in groups, and how many different modes of transport are used in one trip, etc. The cumulative effects of these choices have resulted in observable trends globally. This study will focus on the intersection between gender, transportation, and climate.

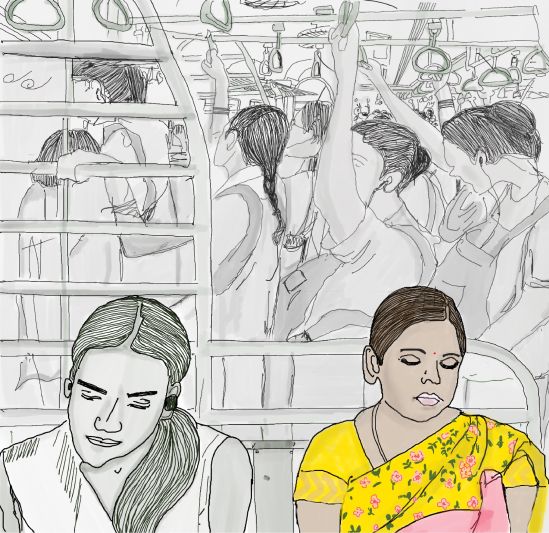

A growing body of literature documents the difference in men's and women’s mobility patterns. As Jain and Tiwari point out, the variation in mobility across the two genders is “largely governed by the triple roles that women play, i.e. earning, domestic and community management responsibilities.”5 Instead of simple considerations like availability and proximity to transit, complex challenges include making more complicated excursions for activities such as childcare, domestic shopping, maintenance-related tasks, etc., impacting how women move every day. Following this arises the fact that women’s trips tend to be during off-peak hours and often carry more than just themselves- dependents such as children or elderly persons or goods and groceries they hold on their way. Women, especially those from lower-income groups, are burdened with greater domestic responsibilities and weaker access to household resources, compelling them to use less expensive and slower modes of transport, often even while hanging out of the train. Thus, women also make different modal choices, tending to use more public transportation than private cars. When public transport is not available or inadequate, they use paratransit, or Intermediate Public Transport (IPT) more than men, and a more significant proportion of women travel on foot, especially in developing countries.6 A working paper published by the World Bank Group in 2021 reveals similar mobility patterns while commuting to work in Mumbai- with greater reliance of women commuters on public transport and walking than men. Men, on average, also travel farther than women to work. The modal share for women is 20 per cent versus men, 17 per cent, for rail travel. For the bus, it was 12 per cent versus 8 per cent, and for walking, it was 38 per cent versus 28 per cent.7

A study in Sweden, commissioned by Vinnova, Sweden’s Innovation Agency and conducted by Trivector, revealed that if everyone in Sweden travelled the way women do, “the energy use and emissions from passenger transport in Sweden would decrease by almost 20 per cent.”8

The preliminary interviews for this study suggest that the trends in Sweden and Mumbai are comparable, with women trip-chaining more and men travelling farther distances by private transport. We, therefore, have grounds for speculation that Mumbai's energy emissions from the transportation sector could significantly decrease if more regular commuters began using public transportation like women. This project has been undertaken as a part of the Women4Climate mentorship program by the C40 cities in collaboration with the Ministry of Environment and Climate, Maharashtra, which builds women’s participation and leadership in the conversation around climate action.

This research is conducted by Vidisha and Anamika who are daily public transport users in their respective cities i.e., Mumbai and Kolkata. They are interested in exploring the intersection between mobility and climate. Vidisha has lived in Mumbai for 15 years and commutes daily using the local train, the BEST bus and the Mumbai Metro. Vidisha's goal is straightforward: to make commuters' lives in Mumbai easier. She bases this on her reflections of her experiences and observations over the years, which are aided by her professional background as an urban designer. Anamika, following her interest in urban built environments, likes to investigate the relationships between a city's inhabitants, its infrastructure, and the surrounding environmental conditions. The study aims to test the claim that women's travel preferences significantly reduce carbon emissions. In order to emphasise the differences in how women travel and the factors that influence their choice, this research intends to record the current travel behaviour of the city of Mumbai by employing a robust public participation process in various neighbourhoods across the city's socio-economic strata, gender and age. The study's objective is twofold- to measure and quantify the effects of diverse mobility trends on energy emissions and identify the infrastructural gaps that hamper the everyday commuting experience. This study will help us identify gender-specific infrastructure shortcomings and compile practical solutions to encourage more people to switch to public transit in Mumbai.

1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mumbai_Suburban_Railway

5 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352146520306517

6 https://smartnet.niua.org/sites/default/files/resources/UNEP_Gender_Report_For_Upload_Med_Rez.pdf

7 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/35248