Goa - Beyond the Urban-Rural Binary

Goa - Beyond the Urban-Rural Binary

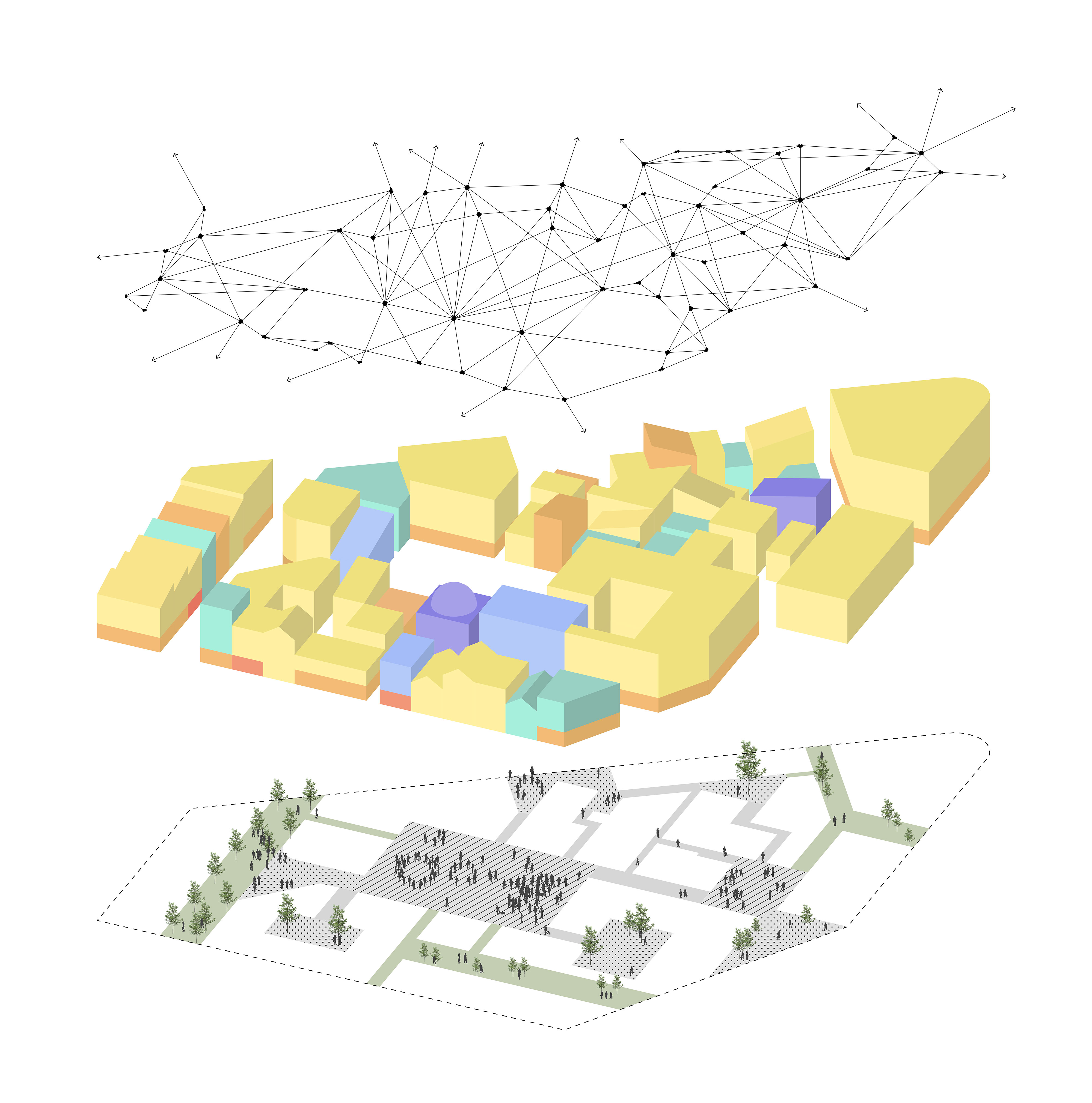

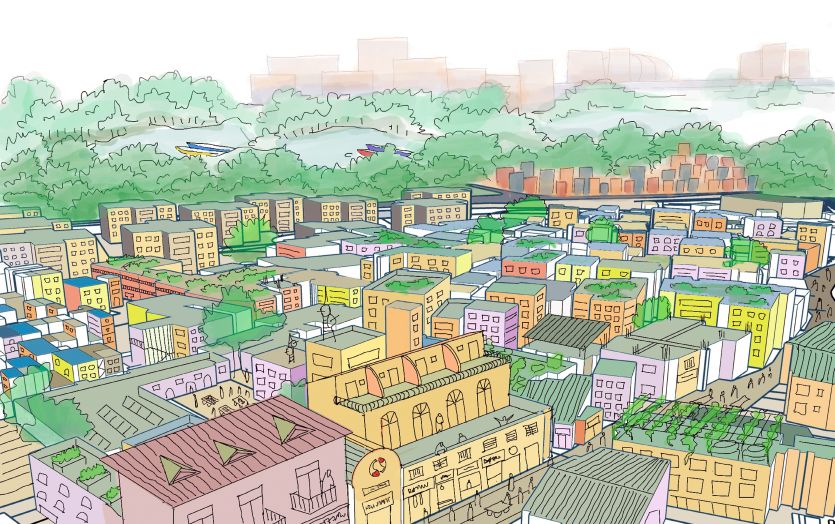

This article proposes an alternative perspective on Goa's urbanism and suggests that the way Goa functions and its spatial distribution is different from the usual forms of urbanism in other Indian cities and States. I argue that Goa has developed in contrast to the common form of centralized urbanism and doesn’t follow the logic of concentration, the general paradigm of urbanization in the West, and most of the world. Goa is located in the western coastal region of India, bordered by the states of Maharashtra in the north and Karnataka in the east and south, while the Arabian Sea forms its western coastline. It showcases a distinctive pattern of urbanization, a Network-like-System representing the coevolution of its countryside and urban centres. Key indicators of Goa's language of urbanism are decentralized, dispersed systems with village republics. Applying a new understanding of urbanism, derived from examples such as Goa, could lead us to a more harmonious future where land use respects all the diverse habitats and integrates the rural and urban areas in a more sustainable manner. Asia could play a leading role in developing and experimenting with alternative forms of urbanism, navigating away from the paradigm of centralized urbanism (induced by the west) and its apparent dysfunctionalities.

To outline my thesis, I will start by presenting some background about colonial impacts on urbanization in India and slowly show the distinctive characteristics of Goa, when compared to other Indian cities. Followed by a brief discussion on the two apparent impulses of urbanization, centralized and decentralized, exemplified through the urban history of two European countries, France, and Italy, thereby reflecting the impact of imperialism on the western urbanization processes. Building on this foundation I will be introducing Goa as an alternative form of urbanism, firstly by referring to its urban history and polycentric growth, secondly by regarding its unique spatial logic which encompasses the urban and rural without the traditional standards of segregation between the two.

To outline my thesis, I will start by presenting some background about colonial impacts on urbanization in India and slowly show the distinctive characteristics of Goa, when compared to other Indian cities. Followed by a brief discussion on the two apparent impulses of urbanization, centralized and decentralized, exemplified through the urban history of two European countries, France, and Italy, thereby reflecting the impact of imperialism on the western urbanization processes. Building on this foundation I will be introducing Goa as an alternative form of urbanism, firstly by referring to its urban history and polycentric growth, secondly by regarding its unique spatial logic which encompasses the urban and rural without the traditional standards of segregation between the two.

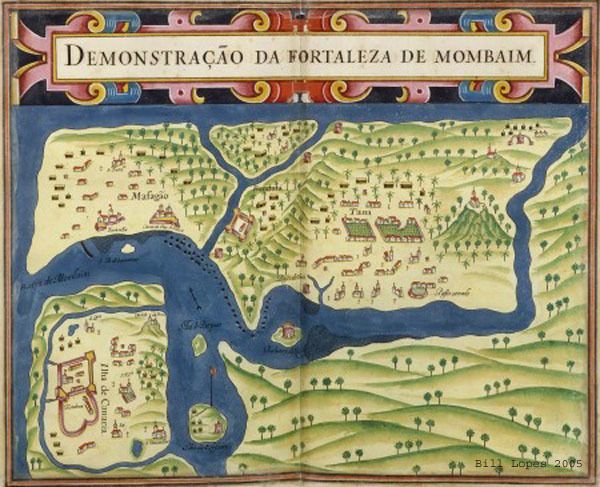

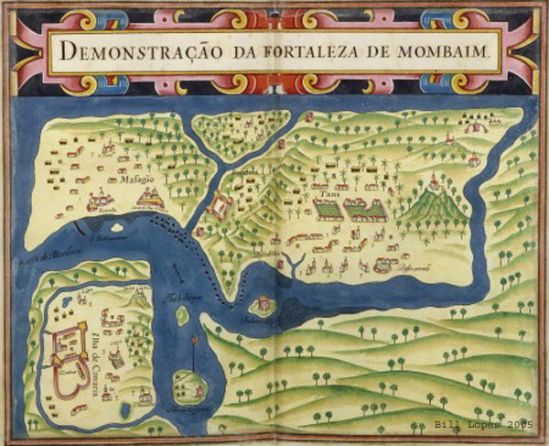

Unlike the rest of India, Goa remained a Portuguese Colony and was not taken over by the British during the 19th century. The acquisition of India by the English had a strong impact on the course of the country’s urbanization. The previously established towns and cities with their specialized economic functions suffered immensely during the warfare and its disruptions which also resulted in a declining local market. The former industrial structures collapsed, and the trade of goods was eventually taken over by the English free traders. The economic slump led to a significant decline in the population, economic status, and political importance of the precedent Indian cities. At the same time, the cities of British origin such as Calcutta, Madras and Bombay flourished and accounted for the largest cities of India at that time. The entire economy went through major changes and other cities had to adapt to fit into the new patterns, commanded by the new rulers. Their ideas of spatial distribution and mobility have shaped the apparent forms of urbanism and types of cities as we can still observe them today (Biswas 2015). Most of what we know today as India had been under British rule, yet the recognition of space greatly differed between different colonial powers, to illustrate diverting ideas of settlement become obvious when we look at the development of Mumbai. It was the Portuguese who had colonized Mumbai in the year 1543 (and Goa) first and it was under their rule until 1661 (Mumbai History). During this period, the Portuguese had mapped out the territory multiple times (Figure 3).

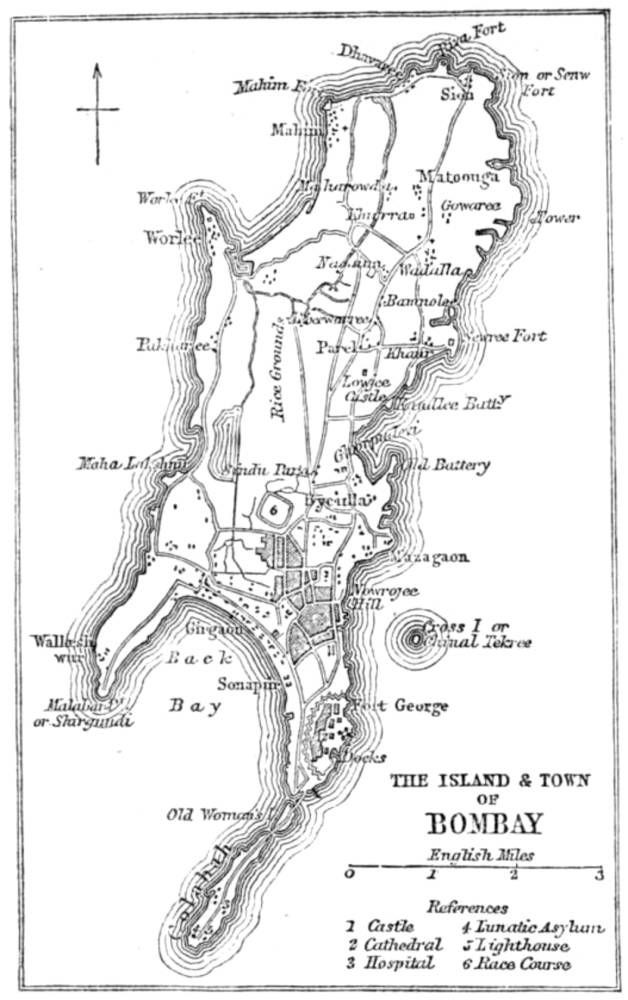

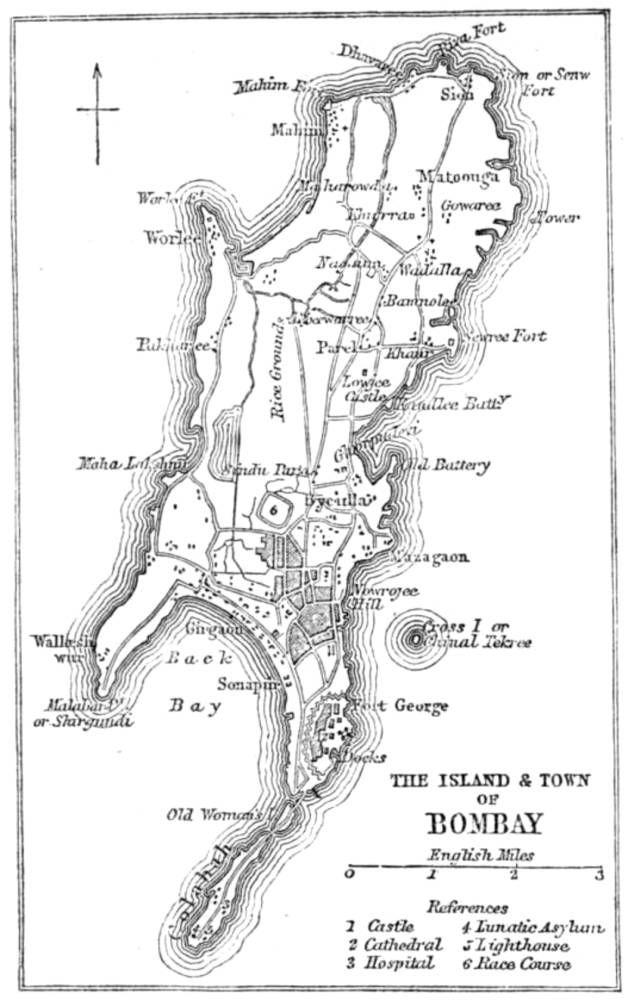

Later Mumbai was eventually acquired by the East India Company in 1668 and was named Bombay. In a matter of seven years, the population of the city rose from a mere 10,000 to 60,000 in 1675 (Mumbai History). The continuous growth of Bombay after its acquisition by the English resulted in an economic boom which set the foundation for the city to become India’s most important industrial and commercial centre (Biswas 2015). This drastic change was not only due to a general increase in population but also to the Britishers' centralized approach of urbanism and capital accumulation, all activities were centralized to the main peninsula of Mumbai, which quickly suffered from overcrowdedness. In Figure 4 we can see that the map of Mumbai (Bombay) made by the Britishers, it only illustrates the main peninsula of Mumbai.

The landmasses beyond the waterways surrounding the main peninsula are not even considered worth representing. Now, if we take another look at the first map, made by the Portuguese (Figure 2) we can notice the detailed illustration of the waterways, which connect the main peninsula with the surrounding landmasses and the various smaller settlements distributed along the water. The water was utilized for mobility and the distribution of activities and settlement took place over a much vaster area of land. Utilizing a dispersed system and navigating through the waterways, even though the population size was much smaller during the Portuguese rule, is distinctive for the general approach to the urbanization of the Portuguese.

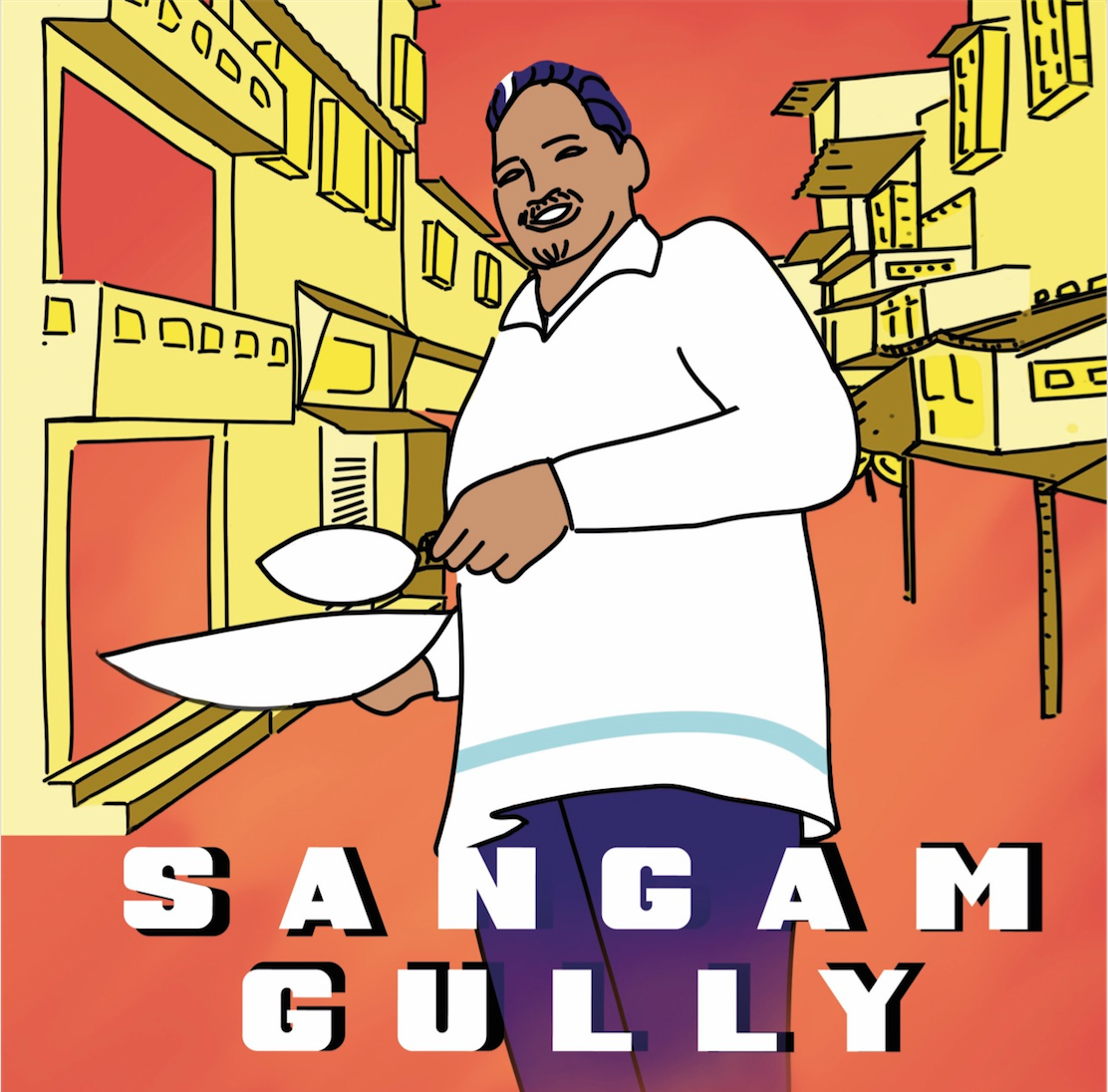

The same approach was applied in Goa. Settlement and multiple activities (trade, agriculture, industrial activities, culture, etc.) happened in many places simultaneously, which resulted in a decentralized form of urbanism. Outstanding for Goa, even today are the many small centres spatially distributed over a vast area, connected and reachable not only by roads, which were built much later but also through the waterways. This network-like approach is typical for Portugal as well. There we find many important cities with diverse functions and specializations, including the capital Lisbon, along the coastline, and hence connected through water. In general, the Portuguese understanding of the spatial distribution of settlements was much wider than that of the Britishers and reflected in a polycentric form of urbanism.

The impact of colonialism on urbanism is also reflected in the countries from where the imperial powers originated. One could even argue that the rise of European settlements was built on colonialism and the capital accumulation derived thereof. Capital expansion, trading, and investment were driven by the wealth accumulated through imperialism and allowed European cities to flourish. Bright examples of urban expansion during this period are France, Spain, and England. Those countries gave rise to big cities like Paris, Madrid, and London. The centralised form of urbanisation became the idealised model of infrastructure and the de facto model of urbanisation in Europe. This development resulted in a rather poorly developed countryside in awe of the inimitable capital. The growth of these megacities quickly became political projects supported by economic concentration, encouraging more people to migrate to these cities. The vision of becoming modern nations made the capital cities centres for global and national migration and national identity. Immense architectural work and infrastructure were developed, and the cities became showcases of advancement for the whole country. Throughout the 21st century, the dominant urbanization paradigm was centralized urbanization following the logic of concentration. The centralization became the integrating form not only for the West but, more recently, largely for the world. Similar developments can be observed in the USA, where New York and Chicago were emerging like global cities. It is evident that the imperial ambitions affected Europe but within Europe, there are also exceptions and countries which reflect a decentralized ethos. For example, Portuguese and Italian economies had developed backwards during the time of imperialism and experienced a different form of urbanism with small cities and villages. Most of their cities have city centres and squares and are evenly distributed over the whole country. Those “nodes” are important for different, oftentimes specialized activities and are interconnected. Overall nature remained more intact in countries where such decentralized urban systems have emerged but at the same time, overly dispersed systems also have a huge range of disadvantages.

Throughout history we have always had these two impulses:

- Centralized forms of urbanism, following the trajectory of one megalopolis

- Decentralized urban systems with multiple growths of cities, each of those cities developing their own identities of the population

In the following section, we take a closer look at two countries, each as an example of one of the two impulses mentioned above, starting with the former.

You can access part 2 here.