Goa's Homegrown Commons

Goa's Homegrown Commons

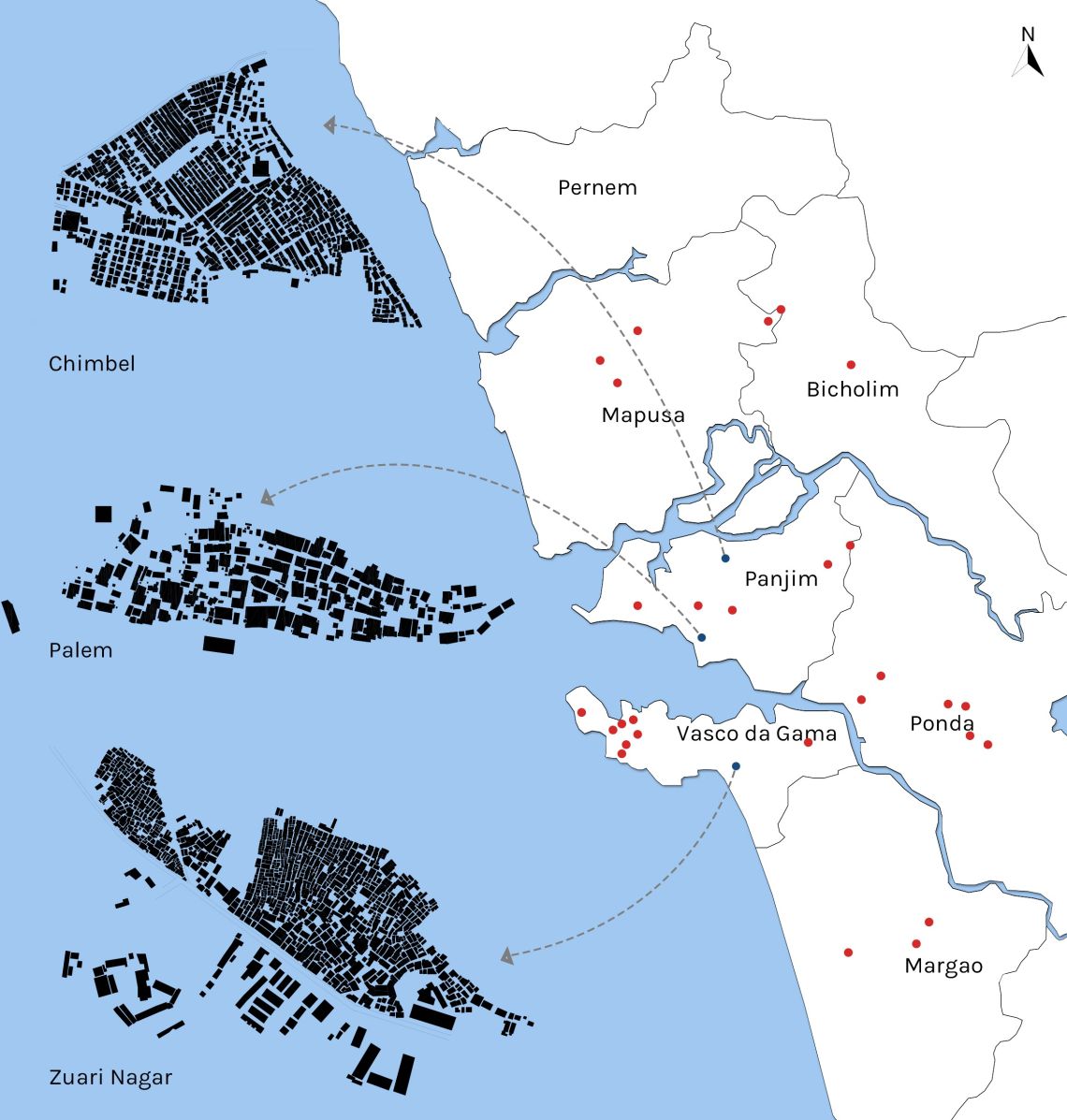

Travellers to coastal Goa never fail to marvel at the dramatic landscapes of open fields, shimmering rivers, sudden expanses of water, rushes of palms, and the cosy dense settlements that characterise the drive to most of its tourist destinations. At the same time, they are also taken aback by the large swathes of bastis and slums that are becoming increasingly visible—like the Zuari Nagar settlement near the airport or the more hidden neighbourhood in Palem, or the official, government-seeded Indira Nagar settlement in Chimbel. There is a certain fragility about Goa’s infrastructure that slides easily into a narrative of perennial decline.

What is often overlooked is that this fragile infrastructure actually had a resilient and fairly robust system that managed to sustain and maintain the landscape and habitats for a long time—but which has been significantly undermined. If the celebrated landscapes of Goa still manage to hold their own in today’s frenzied times, a fair amount of credit ought to go to the institution of the Comunidade.

Coastal villages have to preserve the fertility of cultivable land against the constant threats of salinity. This was historically managed, as in similar parts of the country elsewhere, through local systems, controlled by the first or original settlers and inhabitants of the village. Traditionally known as the Gauncari system, it became codified by the Portuguese into the Comunidade—an elaborate and diverse system of managing local land-use norms, occupancy rights and revenues. It was not simply a patriarchal, nativist institution (although that was undeniably part of its history) but one that was significantly concerned with managing the quality of agricultural activity and local affairs, based on principles of collective ownership and responsibilities.

From the 1960s onwards, much-needed land reforms took place in Goa. Though, as architect Arminio Ribeiro points out, “the post-liberation land reforms failed to distinguish between tillers of privately held lands and that of Comunidades, resulting in the loss of a vibrant agriculture model, revenue and lands. Those Comunidades that had assumed responsibility of maintaining bunds, irrigation networks, worker welfare such as food and housing were undermined by interference from the parallel administrative structure of the Panchayats helped by a new political system.”

Comunidade land allowed non-native villagers (from the region as well as outside the borders of the state) to settle there. It also evolved systems of shareholding for occupancy rights—as long as it was focused on maintaining productivity in the village and no one traded the land. Today, the institution survives but its spirit has been eroded. It mainly comes into the news tied to stories of land grab—either by developers or politicians.

According to Ribeiro, the Comunidade could have continued to evolve into a modern body, shedding its more medieval roots but still doing what it was good at—managing local fragile environments through active human engagement. Just like some Goan villages have evolved into modern entities, which can give cities a run for their aspirational lifestyles, the Comunidade could have evolved into an inclusive, modern system. One that managed local affairs, working hand in hand with democratic institutions like the Panchayats and municipal councils rather than being pitted against them. Its most relevant legacy is one of collective ownership, an attitude that questions individuating or privatising all aspects of the environment. In today’s context, we can imagine how this system could have helped prevent the run-away speculation that is currently degrading Goa’s fabric.

This model of collective land ownership should be of particular interest to urban practitioners and anyone concerned with the growth of slum pockets in Goa. The types of settlements where migrants find accommodation varies greatly across the state, ranging from very old and established ones such as Palem to newer ones that dramatically lack basic infrastructure.

Things may have been better if such settlements had continued in the spirit of collective responsibility, which could give long-term, stable occupation rights without necessarily translating into private ownership rights. If we see privatisation as the only way to regularise settlements, we increase the risk of political manipulation and real-estate speculation.

Systems working in the spirit of local collective ownership, with clearly articulated responsibilities towards the environment, infrastructure, and quality of habitat, could have paved the way for a smoother transition in Goa. The coastal state like any other dynamic economy must find ways of accommodating the workforce it relies upon. Why not seek inspiration for new models in Goa’s own history and vernacular practices?

The article was first published here as a part of the fortnightly column 'Place, Work, Folk' for The Hindu Sunday Magazine.