Letter from a globalised island of Ulleung-do

Letter from a globalised island of Ulleung-do

Amitav Ghosh recently reminded us that globalisation has always thrived on local singularities — and often destroyed them in the process. In his article about the spice trade in the Moluccas archipelago in Indonesia, he describes how small isolated places sometimes catalyse global economic and political interests, and get severely impacted in return.

The South Korean county of Ulleung, which comprises 44 islands in the East, tells a similar story. The main island, Ulleung-do, is known as much for its natural beauty as for being a necessary stopover for South Korean nationalists on their way to Dokdo, internationally known as Liancourt Rocks, which is also claimed by Japan.

The islands are also close to North Korea, which fishes abundantly in South Korean waters. Chinese industrial fishing vessels have made their own leeway into South Korea’s exclusive economic zones (EEZ) in the East Sea.

Murky waters

Territorial claims over Dokdo and the competition between fishermen from various countries in the region give Ulleung a disproportionate sense of global importance. Especially since the economic value of the water around it is declining as fast as its fish population.

The economy of Ulleung-do now revolves more around tourism and there may be gas resources to fetch in the deep sea as well. Besides the nationalists who stop over on their way to Dokdo, many Korean tourists go there to experience the stunning beauty of Ulleung. Just like fish, tourists too need a clean and peaceful environment. Yet, both fishing and tourism face huge challenges. Just like global warming and overfishing threaten the ecology and the economy of the island, speculation and over-construction may well end up threatening the tourism industry that sparked it in the first place.

In an effort to retain an ageing population with little economic prospects on this strategic island, the South Korean government has financed large infrastructure projects. The island has more tunnels than a Swiss mountain. It also has a monorail that brings hordes of tourists to a special viewpoint, a scenic bridge and special promenades in the forest that are fully re-constructed with fake wood. Hotels have been hastily built along the shore with no consideration for their architecture or the landscape.

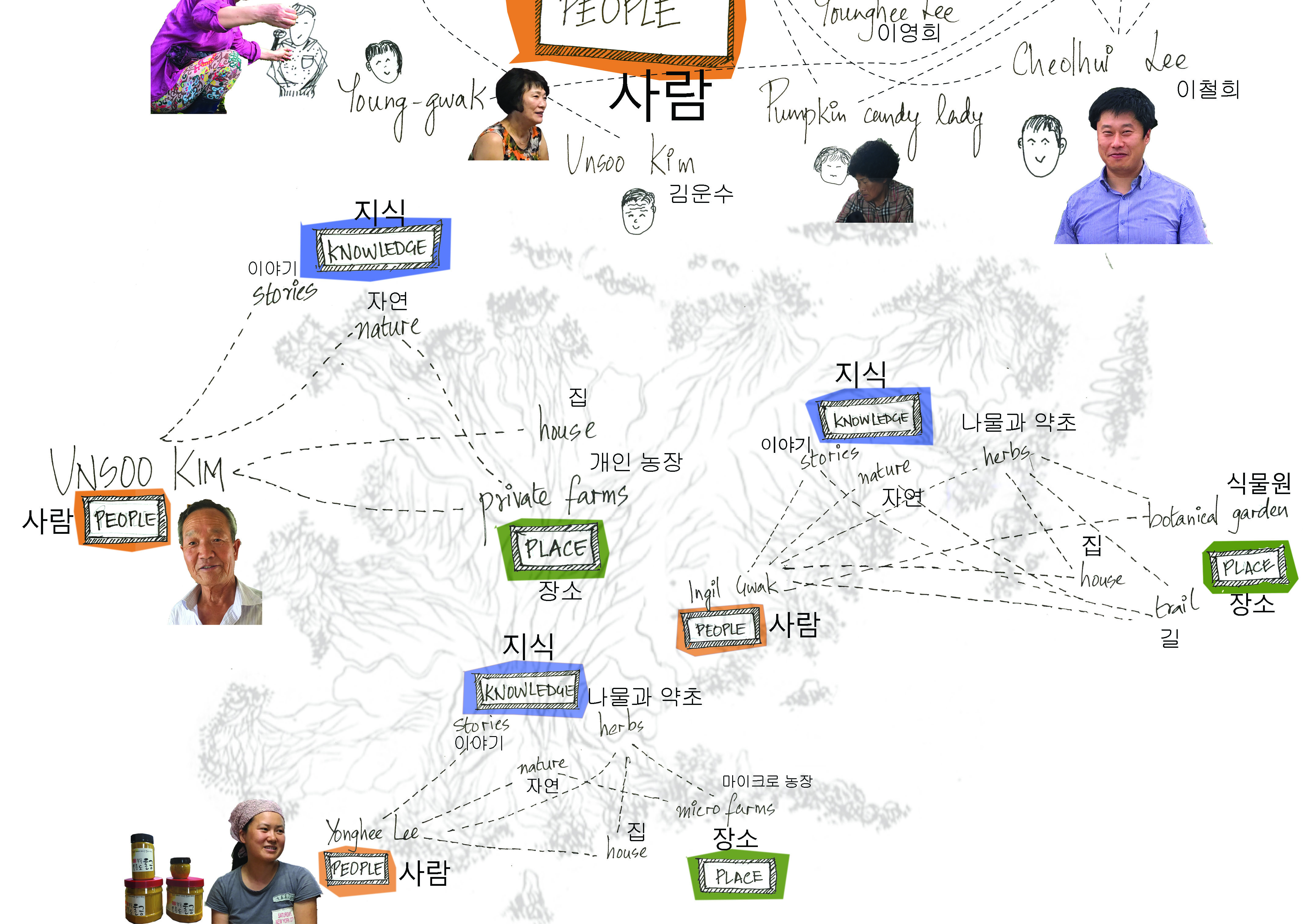

Dozens of native species of plants and fish exist in and around Ulleung-do. According to marine ecologist Aaron Lobo, Ulleung-do is unique in more ways than one. Its isolation has resulted in species found nowhere else in the world. Its communities have co-evolved to use these environments, both land and sea. “Any development plans that ignore these well-evolved links between the local ecology and its people are likely to come at a huge environmental and social cost,” Lobo says.

Rich potential

One of the most striking aspects of Ghosh’s portrait of the Moluccas is the incredibly dense history it packs in. The details of flora and fauna he provides, combine with the accounts of biographies and events to tell us that even the tiniest pieces of territory are rich in potential at every level.

But their life cycles are determined by the choices they make and their ability to do both, use resources and live within the environment at the same time. Colonialism, globalisation and nationalism have all had their say only to leave behind devastated landscapes. What may be necessary is a new form of geo-bio-politics that allows the interests of local populations and the protection of natural resources (which like the sea knows no political boundaries) to weigh in against the strategic interests of nation states.

The article was first published here as a part of the fortnightly column 'Place, Work, Folk' for The Hindu.