The Making of the Koli Jamat Community Hall

The Making of the Koli Jamat Community Hall

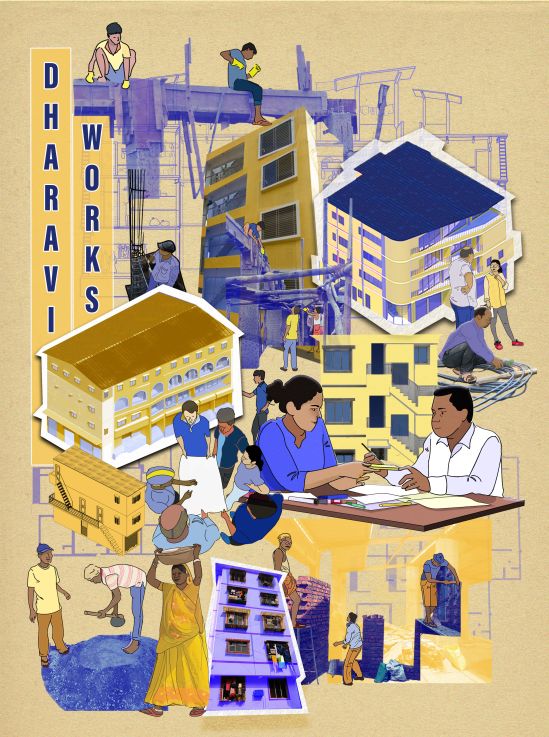

Identity presents itself in various ways in the architecture of Dharavi Koliwada. As a celebration of ancestry with colour, the expression of ownership by scale or even as the otherness of tenancy by typology. Within this context, much like countless villages across the country, construction happens in a network of kinship structures fuelled by verbal design processes. It is common to see contractors and owners on sites designing buildings through discussions, gestures and quick mock-ups. Urbz became a part of this network when the Koli Jamat approached us in December of 2017 to help with the design of a community hall.

The Koli Jamat Community hall was designed as a process rather than as a project. Within a varied group of stakeholders and community interests, the Jamat building took shape of its own accord, only nudged and moulded by us whenever needed. Meetings and discussions with the Jamat, it’s members and the contractors were instrumental in giving direction to the design of the building. Architectural drawings were a method of documenting these discussions, a diagrammatic record of the projects progress. Though the practice is fairly common in Dharavi and other settlements, it overturns the traditional atelier model of thought, followed by drawing followed by construction. It instead distributes the responsibility of architecture and space equally among users, architects, builders and financers. Ownership, is therefore also distributed in the process making it community based in the truest sense.

The Jamat and the contractors were engaged in the design from the first step, initiating a discussion about intent. It was important that the building expressed their identity, the Koli Jamat and Dharavi Koliwada. Despite being here since the first day, the Koliwada is consistently categorised as the other and the Koli’s have not projected their presence onto the city. For most, they remain an anecdotal entity existing inside the city’s geographical limits, but outside its present and future. With a large programmatic requirement, the scale of the project itself proved to be the marker needed to announce Koli presence. The idea of self built was something the jamat wanted to emphasise, instead of hiring a contractor and a team of external professionals to do the job, they believed that the Koli’s themselves had enough expertise to carry out the construction. For this reason, 5 contractors from the community were identified, who came together to work on the project; Each handling a specific aspect of the work.

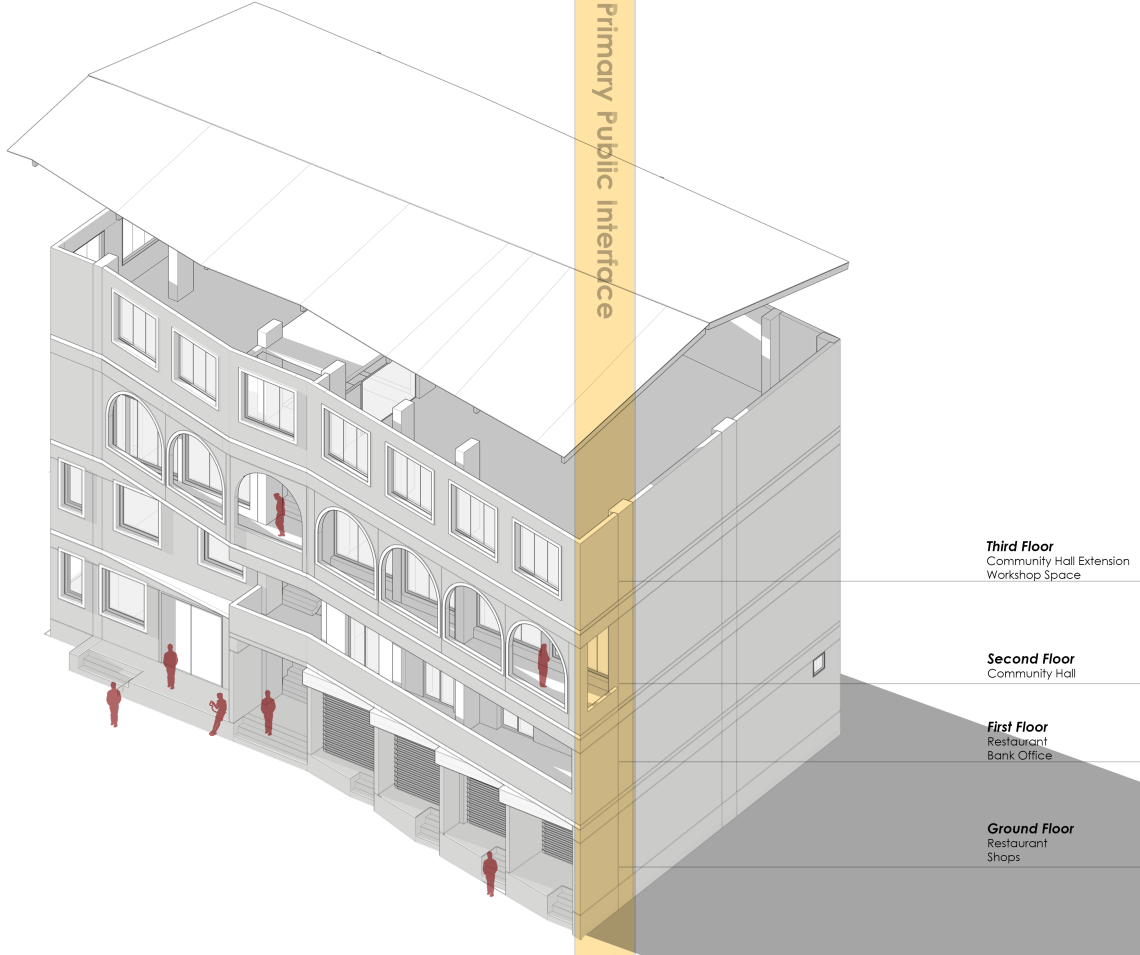

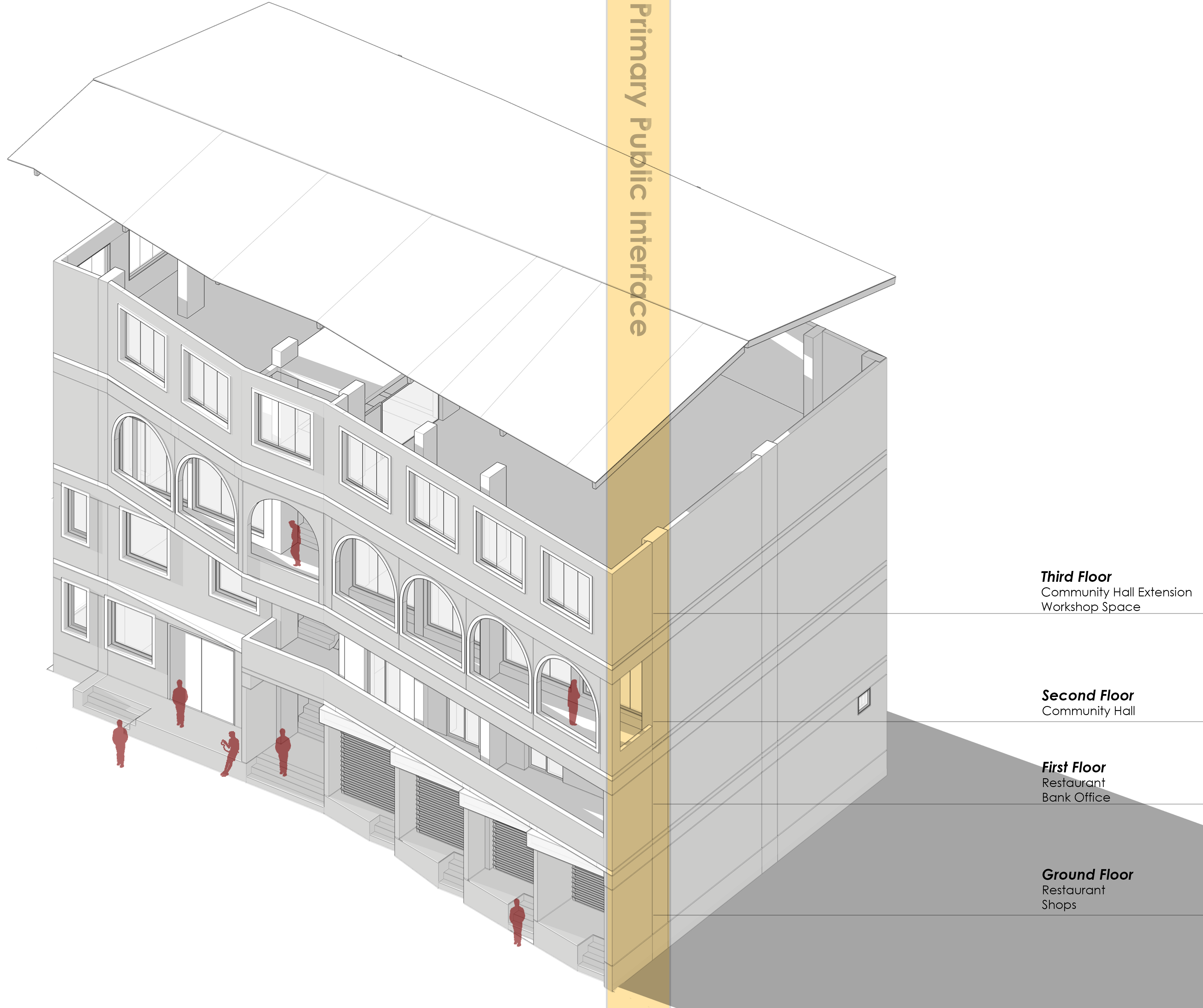

The site, on Dharavi main road was an old Ground floor structure owned by the Koli Jamat Trust, and rented out to shops. The existing shops and the restaurant on site were to be rebuilt for the same purpose and the first floor was made to be let out to a bank and as an additional level for the restaurant. The Second floor is where the Jamat chose to locate their own community hall, with an extension on the terrace. The second and third floors were where the community expended most of their efforts, the Koli Community hall in the process of its construction was visited by almost every person from the Koliwada, to discuss, share ideas and develop the design.

The main facade, facing Dharavi Main Road was essential. In our process of discussions with the Jamat, we evolved the idea of a building that despite its scale, adapts to the fabric of Dharavi. The form follows every kink and turn in the road. Odd junctions are not simplified, but incorporated into its spatial and formal aesthetic. The arches were proposed as large windows to the rest of Koliwada, and as a medium through which the Main Road could get a glimpse into Koli culture. Individual shop owners came in to customise their own layouts and interior spaces, while the Jamat committee made decisions for the community hall interiors in consultation with Urbz and the residents. Programmatic and spatial requirements kept changing as the project moved forward. The restaurant on the adjacent plot, became a part of the project midway, and had to be incorporated into the design. Similarly, toward the end of the construction process, a new floor was incorporated into the program. The top level, previously to be used as a terrace was now to be converted into two separate spaces; one as an extension to the community hall and the second as a space to be rented out for commercial or industrial purposes. With the added floor and the adjacent plot, the project eventually ended up being of a much larger scale than imagined earlier.

It is interesting to see how little and simultaneously how much architecture can do here. Contextual relationships and settlement density act as the background and shape the architecture much before it is realised. The ephemera of the architecture to come already exists on site. The project, as part of this system also took form from contextual conditions and then as it progressed, changed based on the demands and requirements of the community. It is only once it is complete therefore that we are able to frame this process into drawings or text to help us better understand what role we play in it. Is it possible to pre-empt these changes that are proposed on site ?, If it is, would that defeat the motive of participation and constant engagement ? And Is it then really a project designed by the team or is it one designed by the existing context. Engagement at this scale with the Koli Jamat has raised a lot of questions of this nature for the practice and we are attempting to understand and address them as we now make new attempts working on other projects.

The act of construction at this scale, especially in a context like Dharavi is a proclamation of community strength; it involves overcoming bureaucratic obstacles, raising funds and getting support from several stakeholders. And once achieved, it is a means of confidence for others attempting to do the same. Landlords in Dharavi Koliwada have now started discussing their plans for new chawls, shops and mixed use complexes. Maybe now Koliwada could lead the way in a community based redevelopment of Dharavi. The Koli Jamat Community hall is currently near completion, all that remains are the interior finishes and external coats of detailing. The process has taken around 11 months, with 1-2 more months to go, the Koli Community hopes to celebrate Christmas and New Year’s Eve in their new community hall.