Tokyo - Mess is More

Tokyo - Mess is More

The story of Tokyo should appear in every urban planning and design syllabus. Long dismissed as an urban mess, a weird by-product of Japan’s economic "miracle", Tokyo is now gaining attention as a model of urban management. As The Economist put it last month, “perhaps surprisingly, the world’s biggest city, is also one of its most livable." There are indeed lessons to be learned from Tokyo for other cities around the world.

Many writers, photographers and cinematographers, Japanese and foreign, marvelled at the village-like atmosphere of Tokyo. Donald Richie is one of the most eloquent admirers of Tokyo’s meandering streets and human-scale neighbourhoods. He discovered Tokyo in 1947 as a young soldier during the American occupation and quickly fell in love with it. Richie depicts Tokyo as an atemporal organism generated over time by its residents. One which can only be grasped through immersion. He saw Tokyo as a city unfazed by its own destruction, the DNA of its neighborhoods forever that of the villages that once bordered its historical self, Edo:

Compared to the European medieval city, the sixteenth-century Japanese capital was eventually a congeries of little towns, each with some degree of self-sufficiency, each formed so naturally from the common needs that the whole was enriched… Such an urban pattern was perhaps once worldwide, but it is now no longer found in Western cities, where units are welded together to create residential areas, business areas and so on. In Japan, only modernized in the last century, these units remain independent; hence the feeling of proceeding through village after village each with its own main street: a bank, a supermarket, a flower shop, a pinball parlour, all without street names or numbers because villagers don't need them. Each complex is a small town, and their numbers make up this enormous capital. Like cells in a body, each contains identical elements, and the resulting pattern is an organic one. No town planner has yet altered this natural order. (Richie, 1999: 25-26)

Donald Richie describes how Tokyo blends micro and macro dimensions of urban space. It is not a monstrous, inhumane, incomprehensible city, but rather a constellation of many small places. Each with their own internal logic, all of them interconnected to form a complex yet functioning whole. Richie’s Tokyo resonates with Kevin Lynch’s theoretical description of the organic city:

It does have differentiated parts, but these parts are in close contact with each other and may not be sharply bounded. They work together and influence each other in subtle ways. Form and function are indissolubly linked, and the function of the whole is complex, not to be understood simply by knowing the nature of the parts, since parts working together are quite different from the mere collection of them. The whole organism is dynamic, but it is a homeostatic dynamism… So it is self-regulating. It is also self-organizing… Emotional feelings of wonder and affection accompany our observation of these entities. (Lynch, 1981)

Kevin Lynch acknowledges the power of the organic city metaphor, but eventually finds it too literal. According to him “incorporating purpose and culture, and especially the ability to learn and change, might provide us a far more coherent and defensible model of a city”. Lynch prefers to think of cities as evolving learning ecologies. Indeed, what we call a city, especially if that city happens to be the largest in the world, cannot be contained within any boundary, shaped only by internal impulses. It is rather the product of internal dynamics along with larger environmental, economic and political forces - like war, trade, earthquakes and climate change.

Architects and urban designers have often tried to replicate the look and feel of organicity, while ignoring the social, economic and environmental processes that generate organic forms in the first place. New urbanism schemes, for instance, aim to reproduce the low rise and pedestrian typology of incremental habitats, evoking idealized and domesticated versions of the village and the natural environment. Bosque verticals and other token “green” buildings and “eco” neighbourhoods fit in the same category. All for form, nothing for process.

Some experts, like spatial anthropologist Hidenobu Jinnai, believe that Tokyo's urban fabric is the result of cultural specificities. He argues that the city's success depends on its capacity to nurture its special brand of urbanism, instead of copying best practices from the West:

A glance at the history of modern Japan makes it obvious that transplanting the European notions of artfully arranged squares and tree-line streets directly onto Japanese soil has failed to create a space that is both interesting and full of energy. Rather, it is only in disorderly, thriving, and appropriately small spaces, where human feelings and not an expanding vista take charge, that one can find a proper Japanese urban life. (Jinnai: 1995)

Architect Kisho Kurokawa agrees. According to him, the Japanese ability to accept that mess and order are inseparable explains the city's morphology. A city, he says, is “composed of complex and multi-layered relations between an organised structure and the multivalent, heterogeneous elements that can be called noise. The city is always changing dynamically as it continuously incorporates new elements.” (Kurokawa, 1998)

Yet, this dynamic, metabolic vision of the city was notoriously difficult to translate into architectural practice. Kurokawa was a prominent contributor to the Metabolist movement, which produced heroic structures in the 1960s. These were supposed to integrate biological principles, but were actually dead in evolutionary terms. The iconic Nagakin Capsule Tower by Kisho Kurokawa is a case in point.

What makes Tokyo a "learning, evolving ecology" is the multitude of anonymous actors - architects and planners, contractors, artisans, shopkeepers and residents - who operate in each neighbourhood and have built the city, house by house, street by street. Such local d/evolution of urban development strengthens construction capacity at the local level.

The politics of incremental urban development

Cultural factors may help understand Japan's tolerance to urban forms that seem unsound by modern Western standards. Yet, one must look beyond culture to realise the relevance of Tokyo to urban planning and design practice to other parts of the world. Tokyo’s morphology was shaped by local economic life, combined with a tolerant planning framework and relatively supportive urban management systems.

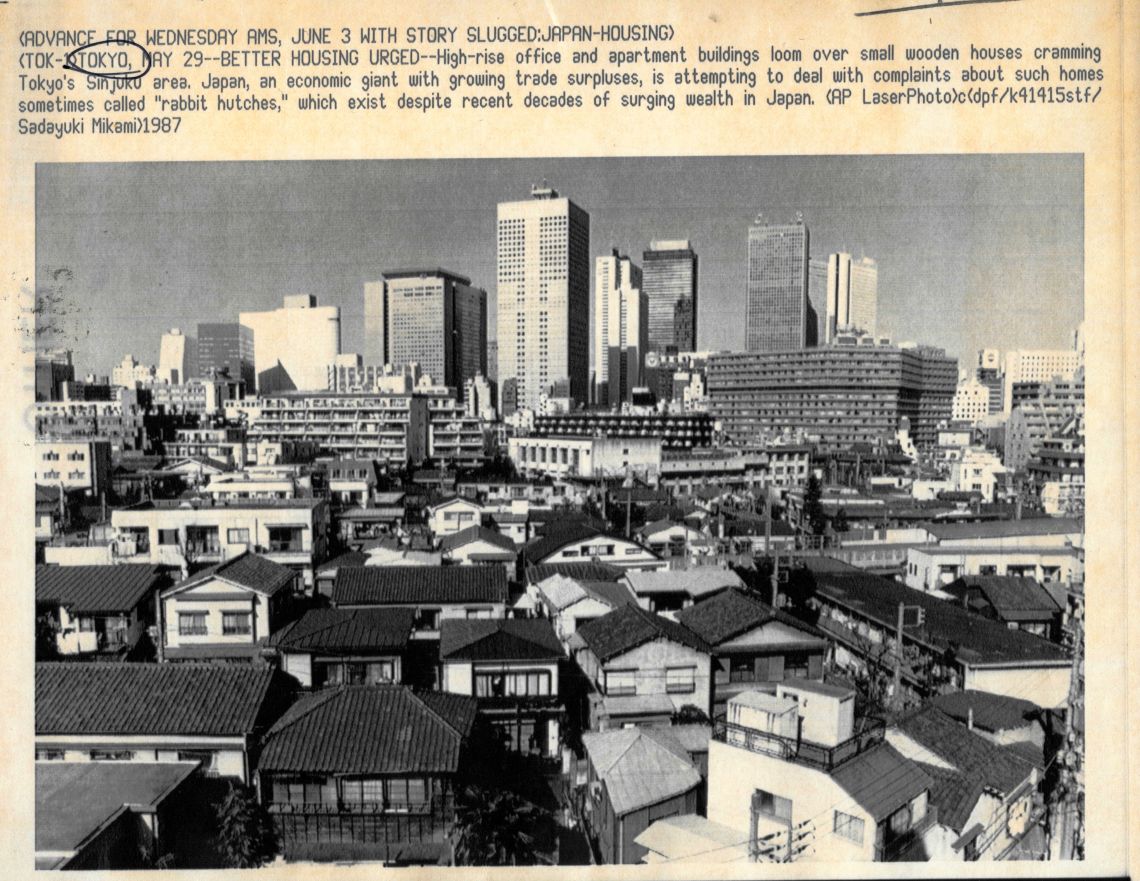

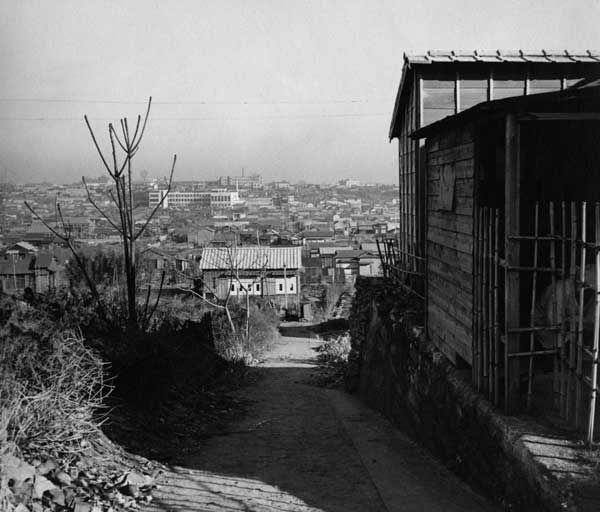

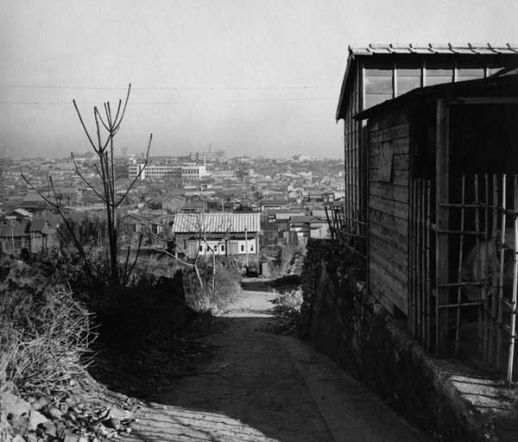

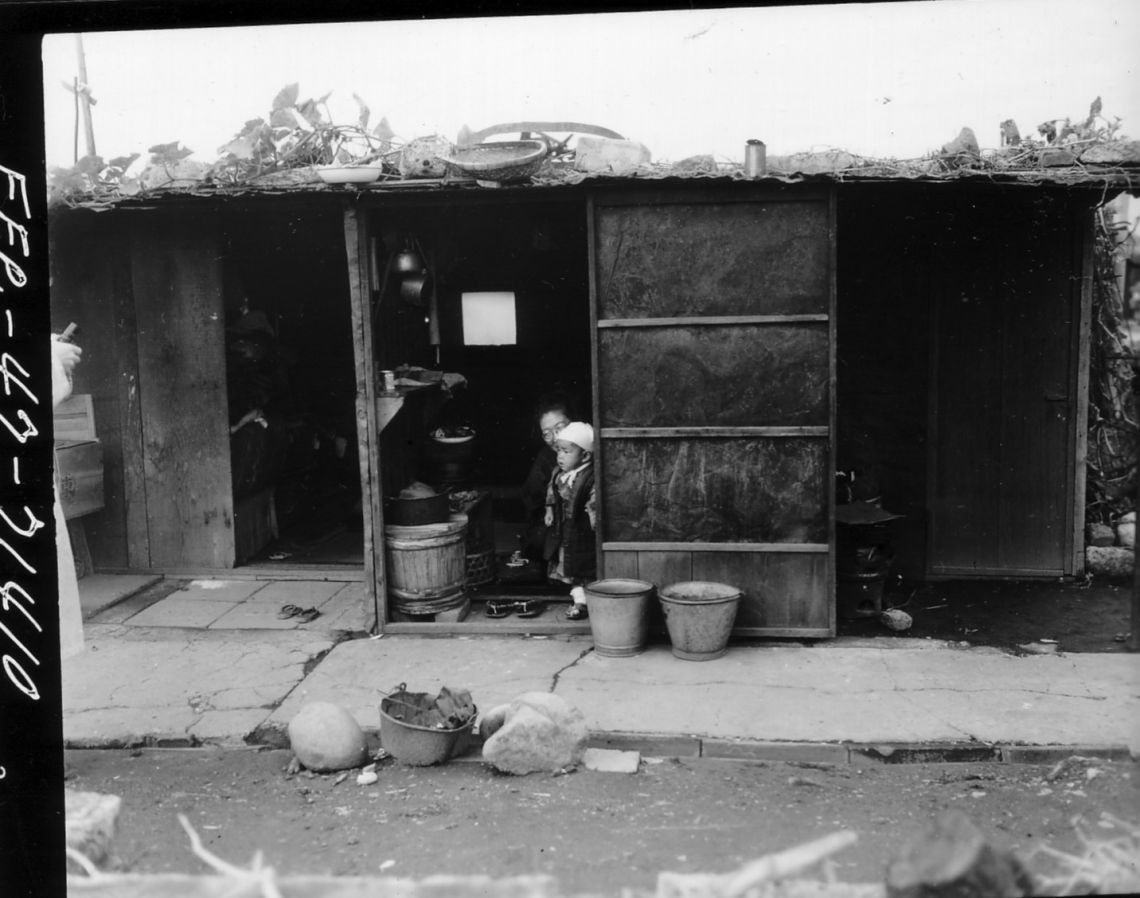

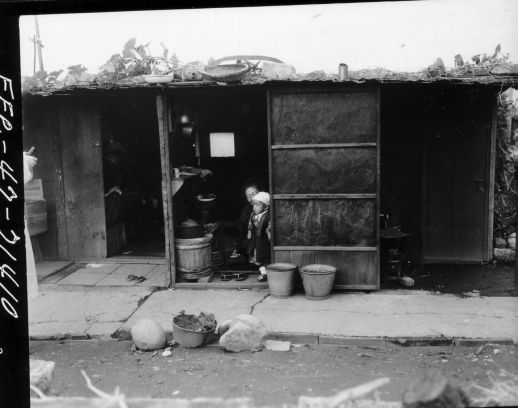

The Tokyo paradox from the late 1960s onward is the coming together of first class infrastructure with an urban typology reminiscent of Asian “slums”. This form puzzled a number of observers, notably from the West, who could not make sense of it. The photo below was shot in 1987 by American journalists to illustrate the problem of housing in Tokyo:

More than the image itself, which is show a cityscape familiar to anyone who knows Tokyo, the accompanying comment reveals a prejudiced gaze. It mentions that Tokyo's houses are sometimes called “rabbit hutches” and wonders how these crammed wooden houses can subsist in spite of surging wealth in Japan. What the commentator missed out is that behind this apparent mess, there are organizing forces at work. Ryue Nishizawa of Sanaa Architects, describe a city that is developing "without a master plan, in a natural way", which may look chaotic but which is actually well managed:

Tokyo appears to be very much disorganized but actually it is a city which works really well. There is no train delay. Every morning huge crowds are moved in a very orderly way from one point to the other. Very few crimes are committed in Tokyo. It is actually very orderly, even if the landscape looks disorderly. Some Westerners come to Tokyo and say this is chaos! Maybe it is true but people manage it very well. (Interview with Seijima and Nishizawa, 2007)

Tokyo provides a powerful alternative to the clearance and redevelopment of unplanned neighbourhoods in cities such as Mumbai, where a majority of the population is said to be living in slums. We have often written about the capacity of local actors in unplanned neighborhoods such as Dharavi in Mumbai to improve their habitat over time through home-based economic activities and local construction practices. Likewise, Tokyo’s entrepreneurs, service providers and artisans were responsible for the reconstruction of Tokyo from the 1950s onward. The city’s residential neighbourhoods are largely “homegrown”, meaning that they were initially built locally with almost no help from the government - which focused its resources on the development of infrastructure and industry.

Local economic development

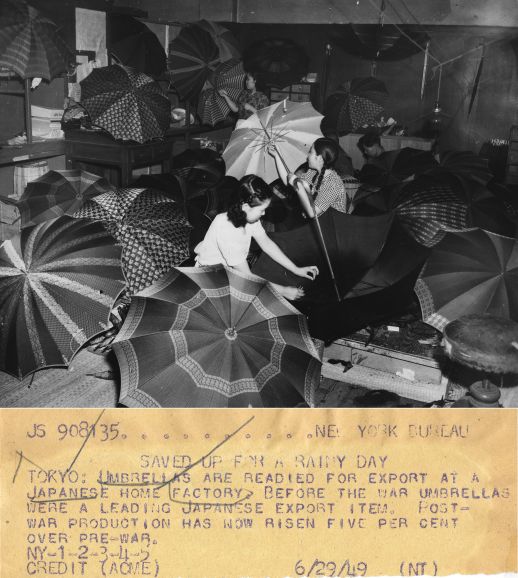

After the war, most businesses were small-scale, family-run, and rooted in traditional social structures. Micro enterprises provided the bulk of employment. Small shops, artisan's workshops, micro-industries and businesses shaped Tokyo’s neighborhoods. While the government employed a large number of people in big infrastructure projects, many more were working as independent masons and contractors building Tokyo’s millions of tiny homes, one at a time.

While the Japanese economy completely transformed in the postwar period, one thing remained constant all the way to the end of the twentieth century: the vast majority of workers were employed in small businesses with less than 20 people, many of them family-owned. According to economist Kohama Hirohis, from 1955 to 1998, the share of the working population employed in small and medium enterprises remained stable at around 70% (Kohama, 2007).

Many houses were rebuilt following the template of traditional Japanese houses, which provided a great flexibility of usage. Residential units were typically used to run small retail businesses and home factories. Conversely, working spaces laid with tatami mats could easily be converted into sleeping rooms or dormitories at night, as was common in villages.

As late as 1981 in Japan “Some 30.6 per cent of the total labor force work in minuscule units … Some three-fifths of small businesses, and four-fifths of retail stores, are "home businesses" in which owners and families constitute more than half the labor force. ” (Patrick and Rohlen, 1986). It is worth noting that, according to Hugh Patrick and Thomas Rohlen, who studied small businesses in postwar Japan, the modus operandi of these units was not competition as much as networking, cooperation and functional integration.

Thus, throughout the post-war period tiny factories spread all over Tokyo, producing parts that were then assembled to produce industrial goods, contributing to the city and the country's legendary economic development. This allowed the incremental emergence of a middle-class that would reinvest a part of its earnings in the improvement of their homes, thus contributing to the overall development of the city.

Whatever was not immediately spent or reinvested was saved in banks and postal accounts, contributing to build Japan’s financial might, allowing banks to lend to the government and corporations, big and small. The government used these savings to finance large-scale urban infrastructure projects connecting neighborhoods through state of the art transportation infrastructures, which contributed to turn Tokyo into an incredibly efficient urban system.

From failed master planning to successful urban management

According to historian André Sorensen, in the immediate aftermath of the Pacific War, the city's modernist planners dreamed of rebuilding Tokyo as an urban system made of many small cities, divided by generous parks, forests and agricultural land. Instead, Tokyo became a huge, dense and contiguous urban landmass without much green space. Planners initially wanted to enforce a compulsory contribution from all landowners of 15% of their land, which would have been used to create greenbelts and public spaces. They also attempted to impose new building codes and strict zoning between residential and industrial areas. None of that happened.

Japan was bankrupt after the war, and American occupation forces didn't think that urban planning was a priority. The government had neither the authority nor the financial means to enforce any of its ambitious schemes. Instead the city was rebuilt on the footprint it had inherited from the high-growth Meiji period (Sorensen, 2002). Land once planned as protected green spaces soon turned brown and grey as hundreds of thousands of survivors built shelters and workshops. Planners were unable to control the city and residents took charge of its development. This level of local autonomy and organization was not new in Japan. It was rooted in the cooperative ethos that prevailed in rural areas.

As a result, there was no real postwar shift in Tokyo’s pattern of development, but rather an acceleration of a developmental process that had started decades ago, and which implied the merging of rural and urban landscape in an apparently haphazard process. In the Meiji period, Tokyo was already a world class city, according to anthropologist Theodore Bestor (1987). The subdivision and conversion of agricultural land continued, and urbanization typically preceded the implementation of civic infrastructure. However, the urban chaos that ensued was mitigated by the capacity of newcomers to establish collective management systems inspired by the places they came from.

Sometimes, it was the absence of planning that provided the biggest push for local initiatives. According to economist Yoshitsugu Kanemoto Kanemoto (1996), plots smaller than 1000 square meter didn't need construction permits and were not requested to follow any building regulation or local guidelines. It is in part thanks to such lenient policies that small owners and contractors became the largest producers of housing in Tokyo, all the way to the 1990s.

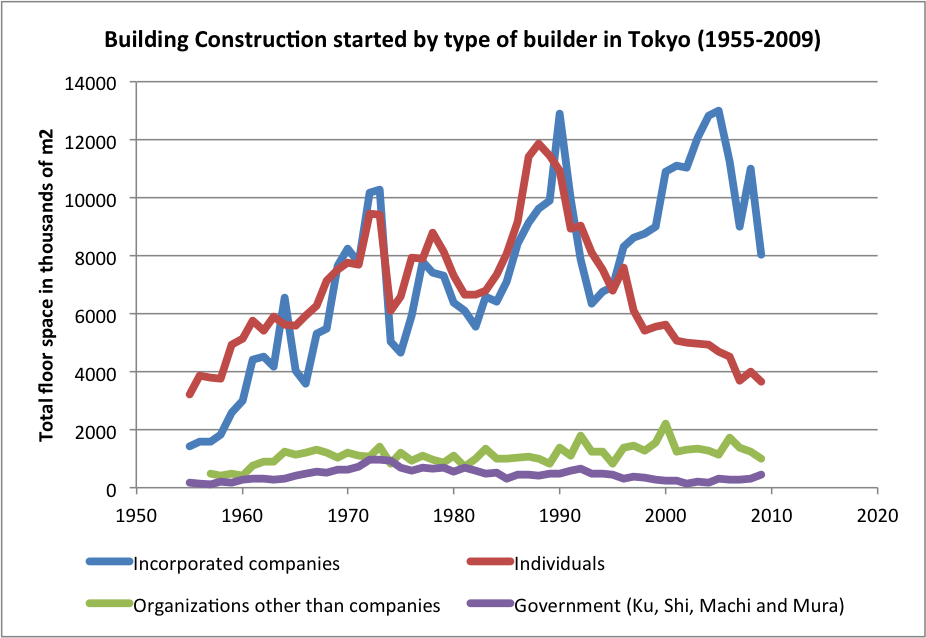

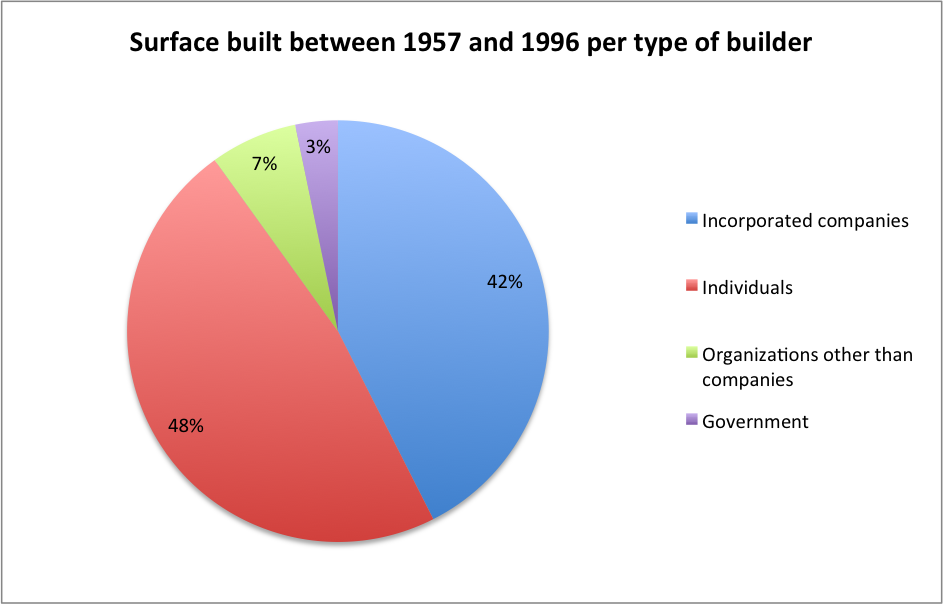

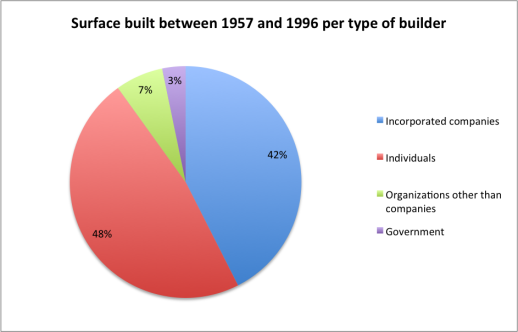

According to data from the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, from 1957 to 1996, non-incorporated individual landowners have built more floor space than large-scale corporate developers and the government together. Families who invested in their own homes and local contractors were the main agents of the urban development at the neighbourhood level. Thousands of local, non-incorporated builders and artisans specialized in small-scale construction.

Affordable housing through local construction practices

This kept construction costs low and contributed to generate a hugely diversified housing stock in terms of style and quality (Waswo, 2009). This diversity is still apparent in low-rise residential parts of Tokyo today. It was not until the 1990s that the government revised the Standard Building Law (Sorensen, 2011) and essentially killed the hugely dynamic market for the construction of small houses. This was done in the name of safety in the context of Tokyo's dangerous seismic vulnerability. Local construction practices were not without their shortcomings, but they did manage to produce a massive amount of affordable housing in one of the most expensive cities in the world.

According to historian Ann Waswo this form of laissez-faire was not simply the result of an incapacity to plan, but also an integral part of the government postwar housing strategy. The “myriad small building companies and a few large, industrialized construction firms” constituted “the vital “fourth pillar” of housing policy”:

Smaller companies tended to specialize in the building of traditional wooden single-family dwellings in both urban and rural areas of the country, the re-building of traditional dwellings that had been destroyed in natural disasters or merely come to the end of their normal lifespan and the building of wooden apartment houses in or near cities, to take advantage of the market for fairly inexpensive rental accommodation among urban newcomers and newly formed urban families. (Waswo, 2002)

Individual contractors and artisans, hired by small homeowners, were responsible for developing most of Tokyo’s urban fabric from the Meiji period all the way till the end of the twentieth century. Far from being a fading memory, this aspect of Tokyo’s postwar development is still very much visible in the city. Small contractors were not merely building traditional homes but also adapted their techniques and adopted new materials. In this respect, the construction sector mirrored the evolution of the manufacturing sector in Japan, which managed to remain relevant throughout the twentieth century by constantly upgrading skills and technologies. According to economist Takeshi Hayashi, “technological transformation in Japan took one of the following two paths: (1) modernizing traditional technologies, (2) making modern technologies traditional” (Hayashi 1990)

From the government’s perspective, the development of small rental units on a large scale reduced the need for public housing. Small houses responded to the need of single-occupants and young couples, and also served as a last resort option for families looking for affordable housing. The tax regime favored the construction of new homes over the restoration of older ones. This helps explain why homes in Tokyo were typically built to last for about a generation and why neighborhoods are, till date, always bustling with construction related activities.

Standardization vs Confusion

Loose zoning regulations allowed the spontaneous merging of residential and economic activities. Tokyo’s neighborhoods were teeming with industrial and commercial activities throughout the last part of the twentieth century. Everything merged and mixed in ways that responded to the immediate needs of the users. This generated serious environmental concerns and zoning was used to segregate polluting industries from residential areas (Sorensen, 2011). However, it was never used to fundamentally re-organize existing urban space along functionalist lines as happened in Europe and the US. The 1978 Standard Building Code recognized mixed land use as a reality of urban development and adopted a rather pragmatic stance towards it:

Of course from the point of view of standardization or purification of land use or land use districts this is not a favorable phenomena but, for example when part of the production process of textiles takes place in the home as a cottage industry, and thus one part of a residential home is used for this purpose, which is not uncommon, it is thus possible to give authorizations recognizing that, limited to a particular model, construction of this sort may be allowed in residential districts. (Mizukoshi, Standard Building Code, 1978)

The use of words such as “standardization” and “purification” to qualify a well-zoned city attest of a bias against mixed-use of urban land. The prevailing idea at the time, in Japan as in Western countries, was that zoning urban spaces along functional lines would increase efficiency and quality of life. According to the authors of the code, zoning would also make the city more “peaceful” and “easy” to navigate. The absence of zoning would result in a “confused” city (Mizukoshi, 1978). As we have seen, however, "confusion" may not be such a bad thing - it merely means "with fusion". This "confused" state allowed the emergence of a mixed use and human scale morphology that makes Tokyo such a liveable and lovable city today.

While many neighborhoods in Tokyo were (and are still being) destroyed to give way to large-scale infrastructure projects, which have always been seen as some kind of national cause in Japan, the approach to hyper-dense, low quality, haphazard settlements has generally been integrative with an emphasis on retrofitting them and allowing them to improve over time. This is why we can see high-tech, well-managed, attractive versions of the same neighborhoods that were once shanties.

Unfortunately, even in Tokyo homegrown neighbourhoods are under constant threat. Jannai laments the disappearance of what he calls Tokyo’s “neo-alleys” in some of the city's central areas:

the modern city continues to grow relentlessly, thriving on one “cruel” remodeling plan after another. Whole city blocks are often covered by one huge building, leaving neither interstices nor space to the rear. The word town once connoted streets defined by houses with storefronts, which created a confused –but nevertheless unified– space. In the process of urban rebuilding, these houses were replaced first by commercial structures, then by elegant office buildings. No longer is there room for the vulgar elements of the city –shops, restaurants, and other “immoral” businesses– except underground… Such a development is no doubt the symptom of an urban civilization distorted by the incessant pursuit of functionality and efficiency, most clearly embodied in the principle of “all yield to the automobile” that now governs our lives. It symbolizes the defeat of the human elements of the city. (Jinnai, 1995: 131)

The concept that neighborhood life needs all kinds of function in close proximity, with a dose of improvisation guaranteeing a diversity of form and function, became mainstream only in the last decades of the twentieth century. For a good part of the 20th century, planning was by and large dominated by a modernist discourse that considered that visual order, efficiency and quality of life came about through master planning. Alternatives were popularised by the likes of Jane Jacobs, who echoed the voices of Patrick Geddes and others before her. In Tokyo, much of the homegrown fabric survived, thanks to its embeddedness with local economic activities, as well as cultural sensitivities and local management systems.

One hears Donald Richie whisper - “fortunately!”