Top of the World: Amrut Nagar

Top of the World: Amrut Nagar

Nestled on the hillocks in the eastern suburbs of Mumbai, Amrutnagar, Ghatkopar paints a figurative picture of the city; where affordable housing is scarce but people have tweaked the system and the land to achieve the best possible results in the given circumstances. The airborne traveler gasps at the sight welcoming the landing craft. The favelas of Rio come to mind, associated as they are with images of poverty and violence. They seem to say “welcome to Slumbai!”

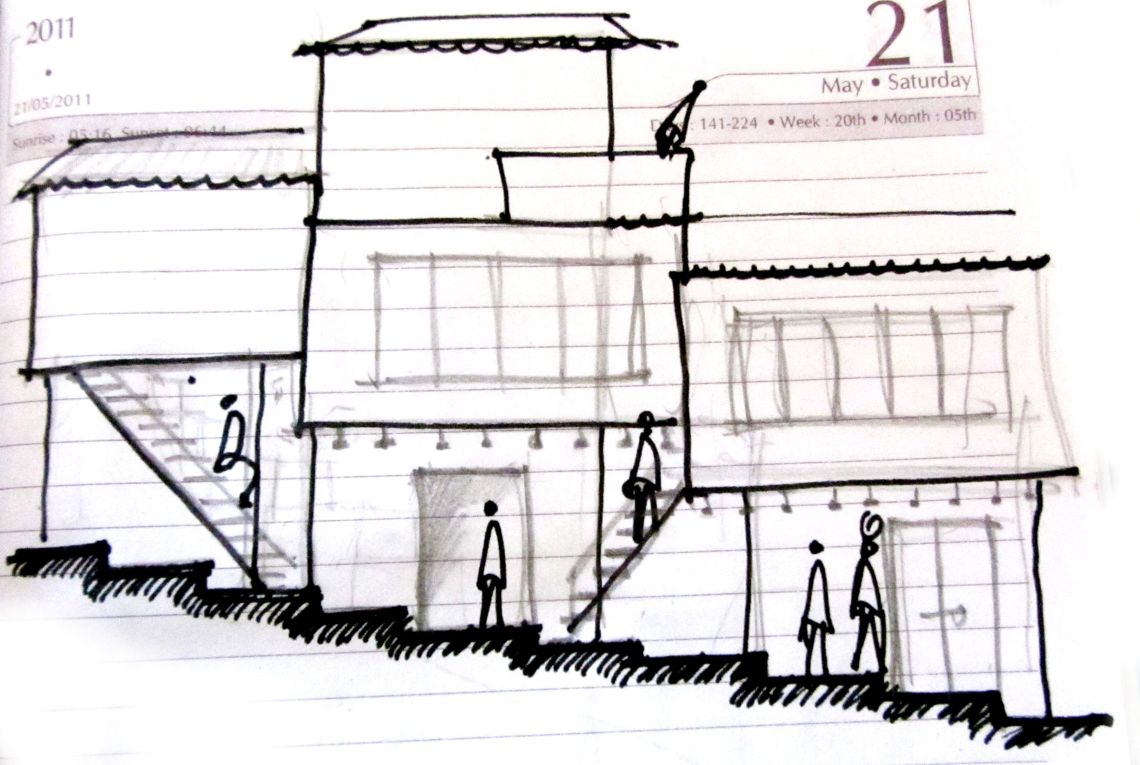

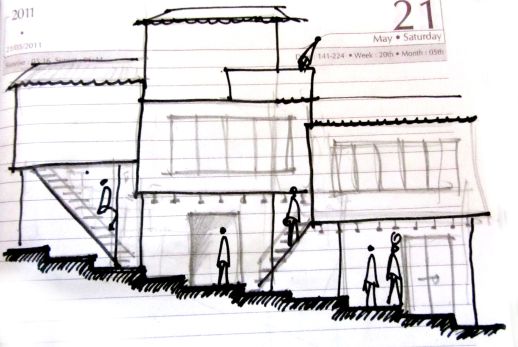

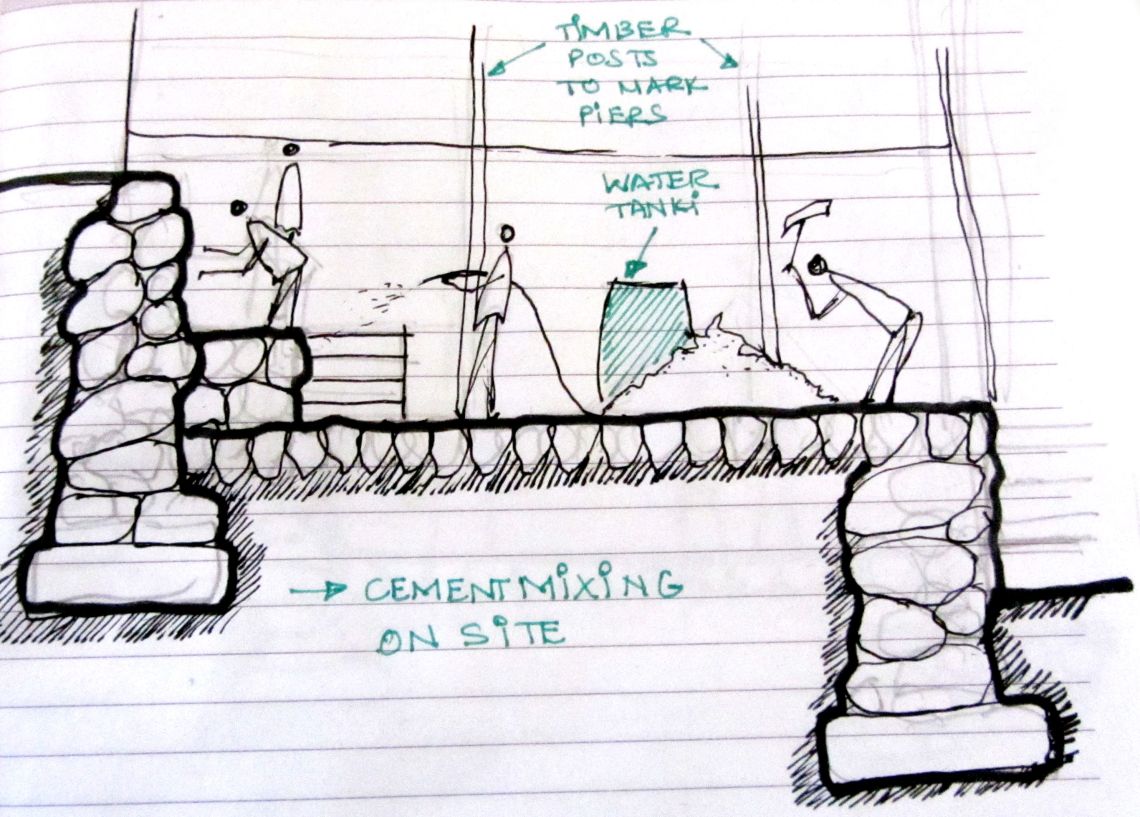

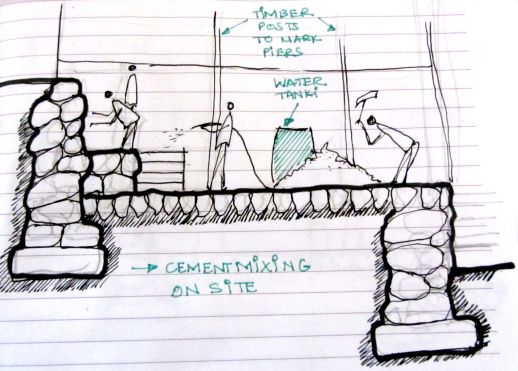

The view from the plane doesn’t do justice to the pertinent housing typology devised by the locals. The housing in this hilly terrain embraces the topology. The rocks dug from the hill are used to build the foundation of the houses and the retaining wall that prevents landslides. The natural slope helps with drainage. Porches acting as public corridors are reminiscent of the quintessentially Bombay “chawl” typology. All houses are oriented in the east-west direction for maximum light and wind. Most of them are only ground floor structure, which allows everyone to enjoy one of the best views of the city. From the hilltop one can see planes landing into Mumbai airport. Catherine Boo may have reported what she saw “behind the beautiful forevers”. This is above.

The homes on the hill are said to be illegally constructed, yet occupancy rights in the city are often more a political question than a legal one. The area we visited was a relatively small 13.5 acres hill called Ramnagar, part of the larger settlement Amrutnagar. With a population of 12,000 locals, this Marathi speaking population is the vote bank of the rapidly rising political party ‘Maharastra Navnirman Sena’ (MNS) which promises to be the guardian angel of the Marathi Manoos. It was previously dominated by the Shiv Sena, the original sentinels of the Maharashtrian community. However, there are a good number of people from other communities as well and the residents are quick to point out that people of all denominations and ethnicity reside here. The locals who have no expectation from the governing bodies try their level best to be in the good books of the local political party workers, as they fear demolition on a daily basis. The cost of constructing a house is very high, due to the hilly terrain and residents usually spend their annual income on a basic house with four walls and a roof.

An estimated 4000 houses are built on and around this hillock and almost all of them are ‘pukka’ houses. 2000 are above the drainage line and the remaining 2000 below. Since the settlement emerged before 1995, it is liable for the SRA scheme and several redevelopment projects are an ongoing feature in the area. One graphical representation of the mandatory 269 sq feet redeveloped flat by the local builder shows a flat screen TV, contemporary furniture and modern art on the walls depicting a certain conception of what urban life should be about. The politician-builder nexus is well known. A SRA scheme can be force d upon anyone and residents are aware that the only way for them to get a legitimate house in the near future is their own hard work and destiny.

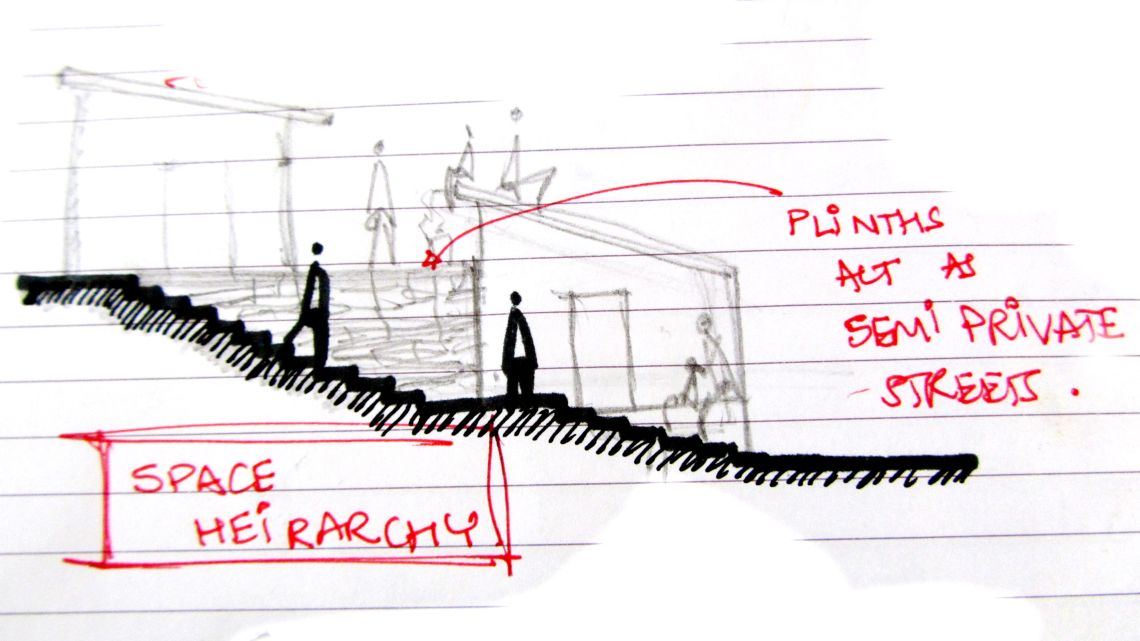

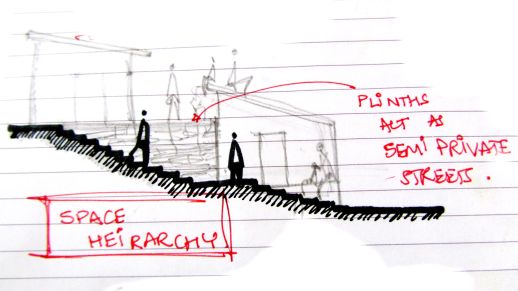

An interesting feature of this settlement is its road hierarchy. With no vehicles able to go up the steps of the hill, the only mode of transport is human and animal. The hilltop crest has several donkeys grazing, ready for whatever work may come up. Every house has a patio facing the city which acts as internal street whereas the steps winding down the hill act as the main road. Constructing a house uphill demands huge labour charges. A minimum 60 bags of cement, 30 bags of sand and 5000 bricks needs to be carried on foot. The labourer charges Rs 100-150 per bag as transport fee which doubles the cost, and a basic house costs around Rs 1.5 lacs. The cost of construction is higher because of use of relatively expensive materials and one extra floor as loft. The loft is usually rented to outsiders for Rs 2000/- a month. The cost of buying a 10 x15 sq ft house is around Rs 15-20 lacs. The local labourers called mistris who are experienced artisans in this field and usually inhabitants of the neighbourhood, are directly hired on daily wage basis for construction which usually last 15-20 days. The houses downhill are higher, have a larger footprint and are more ornate.

The settlement has several temples, public squares and courts, social mandals and groups on its way up and a bustling commercial street at the foothill. Commercial enterprises thrive mostly downhill, as goods transport is tedious and expensive uphill. However economic activities take place in homes as well. The dominant community which has largely migrated from the Malvan regions around Goa, work outside in the city. Most men do office jobs like data entry, peon, clerk or work in private security agencies. Women are mostly housewives and some of them work as part time maids in the neighbourhood buildings. They mostly wash utensils in various houses. A few homes do economic work like assembling parts for some manufacturing activity or the other or simply providing service at the village level. The average male income is Rs 7000-10000 whereas women earn Rs 2000 per month as maids. The area doesn’t function as intensively as the tool house clusters of some other settlements in Mumbai. They pay a monthly rental of Rs 170-220/- to an NGO for 25 minutes of daily water supply, spend around Rs 200/month on mobile phones, Rs 350/month on cable TV connection and some even spend Rs 200 on monthly internet services.

An interesting learning from Amrutnagar is the way people have organized themselves, developed construction technology and housing typologies without help from outside and how they go out on their own and innovate systems to make their life easier. There is a real sense of vernacular urbanism here. Construction techniques in Amrutnagar are unlike any parts of the city that we have visited. They are suited to meet local needs and means. Even without security of tenure and with very limited servicing by civic authorities, citizens have managed to look after themselves and their sheltering needs fairly well.

As we climbed to the summit of the hillock, beyond the settlement, we found the landscape and atmosphere becoming gradually more relaxing. People sitting outside their homes, enjoying the view and the breeze, firmly committed to the quality of life they were living. They claimed there were no mosquitoes, since water slides away leaving no stagnant pools around. They would not want to go anywhere else.

A temple built in 1957 dedicated to Khandoba looms over the hill. The sleepy priest-guru-founder lounges around a charpai. He used to be a mechanical superintendent at the Bhabha Atomic Research Center, turned to spirituality at a young age and built the temple with his hands. A labyrinthine structure with a maze leading to smaller shrines, leads you to the other end of the complex and into a landscape that is anachronistic to everything else we had seen. Lush green grass, pigs and donkeys loitering around. A pathway that seemed to lead to dense foliage, with the promise of a forest adventure.

We land up at the other end, past a hidden cricket field known only to the local kids, the view of a shooting range and a stone quarry, walk through the foliage politely turning away from stray people going to the open-air toilet (no smell – thanks to the pigs) and come to a tarred road and a helipad! Beyond the trees lies a gate and behind that the ‘illegal’ neighbourhood of Hirandanai Gardens can be seen. A city built on subsidized land meant for the poor, with no threat of any demolishing of any kind facing its destiny.

From the point of view of Dinesh, the boy taking a stroll with us, the view from the hill helps him gain perspective on life. Somehow the view, the peace, the trees remind him that a city can potentially provide you with all kinds of habitats. He knows it is a luxury to be able to walk up to a place like this. Right now it instigates him to return to his native village in Benares, so reminiscent is it of a memory he has from there. In minutes though, as he trundles down, he is absorbed into the bustle of the neighbourhood. He points to his father’s tailoring shop and the direction of his college. Back in another world. He is living in a transit camp now. An SRA tower is coming up to relocate his family. Will he stay on? Will he go back? As long as choices remain, all possibilities exist. Somehow one gets the feeling, as the neighbourhood transforms into tall vertical buildings, that the choices which enrich his simple life are diminishing, and diminishing too fast.

More photos and sketches here.

This article was written by Megha Gupta with contributions by Shardul Patil, Rahul Srivastava and Matias Echanove