Planning without colonizing

Planning without colonizing

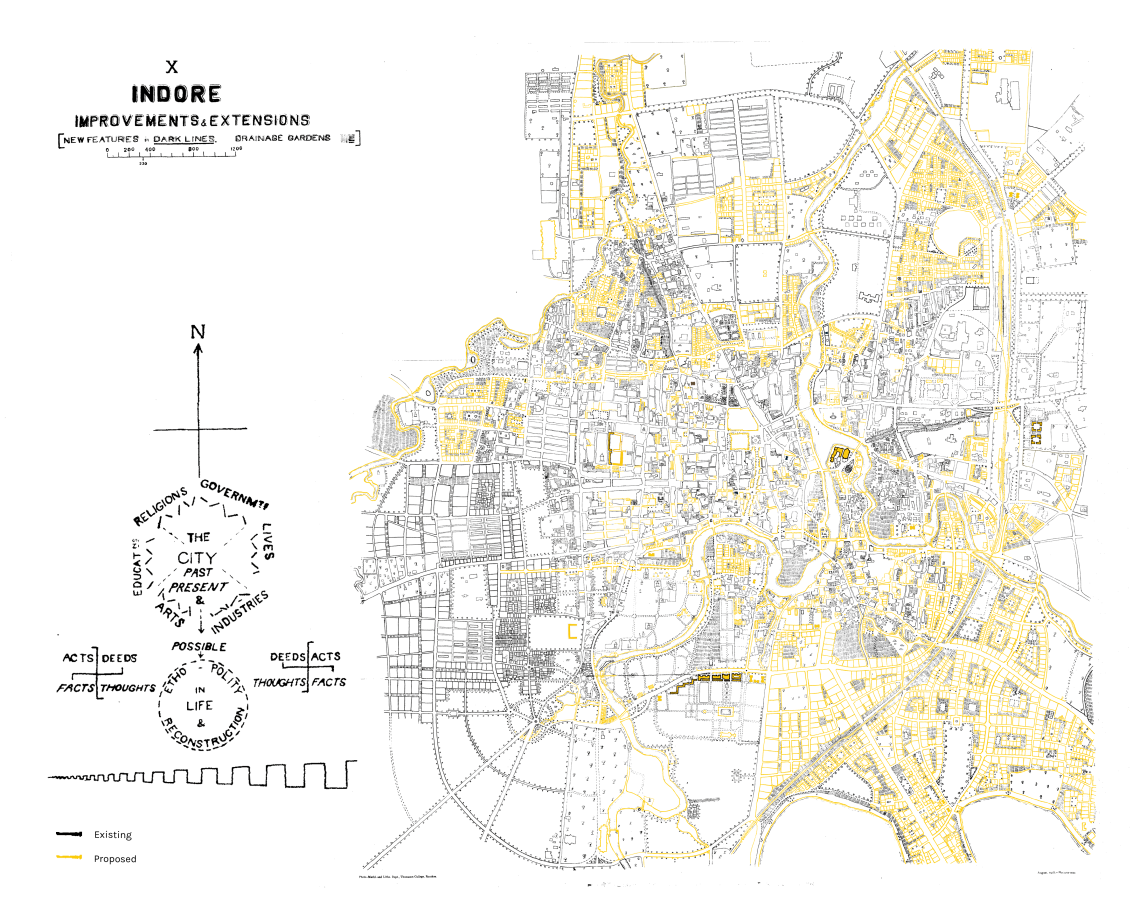

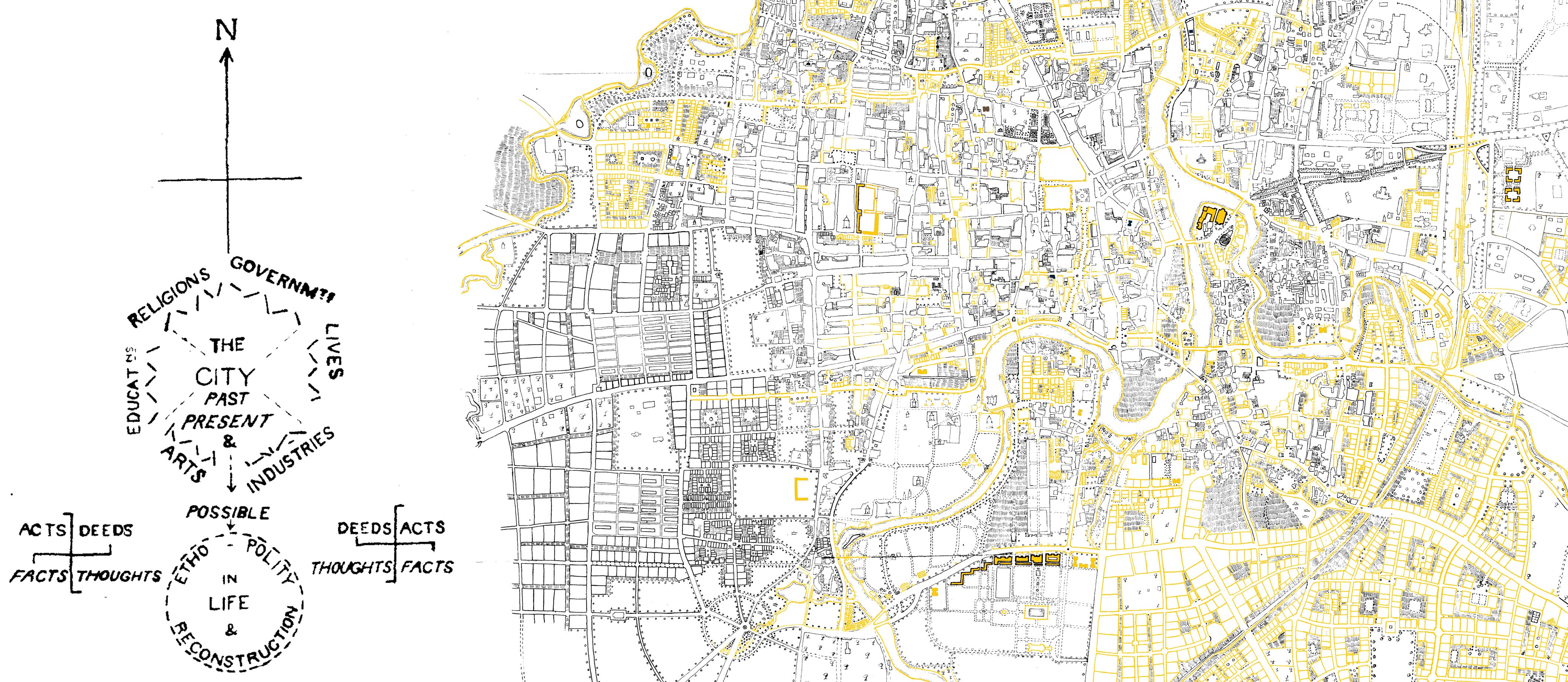

It is fascinating to do an archaeology of urban plans in cities with deep histories of civic engagement. It gives us an idea of how memory, policy and intent lose themselves over time and condemn us to make the same mistakes repeatedly. Take a city like Indore for example. None other than the famed urban planner from Edinburgh in the early 20th century, Patrick Geddes, cast his careful and compassionate attention on this city that was the centre of a royal kingdom. With his Scottish, anti-colonial roots, he was sharply critical of the then pervasive English tendency of looking down on local civic practices and blaming things on native habits.

His ethnographic eye left behind a detailed portrait of a city, its neighbourhoods, streets, alleyways and productive capacities along with a patient diagnosis and suggestions for its future at a time when few Indian cities paid attention to these matters. In the post independence era - the city has been the site of several award-wining projects, from the beautifully planned Aranya neighbourhood by B.V Doshi, to Himanshu Parikh's Slum Networking initiative most notable among them. And yet today one periodically comes across the same old stories about slum demolitions and slum rehabilitation projects gone wrong in the city with everyone complaining - from the government to dwellers alike.

In the early twentieth century, the royal rulers of Indore invited Geddes to help rid the evils of plague and other diseases that infested the city, not unlike many around the world at that time. As was typically the habit of authorities, they mostly blamed it on the so-called bad habits of the local residents – something that Geddes had a strong objection to. According to Indira Munshi, an ex-Sociology professor of the University of Mumbai (the department that Geddes himself founded), he painstakingly pointed out that most residents in fact kept their homes and streets scrupulously clean and it was really the faulty street layout of some neigbhourhoods which lead to water-clogging and the accumulation of dirt. Not unlike the situation in many urban contexts even today.

Munshi goes on to illustrate Geddes’ deep engagement with the city’s civic consciousness by detailing a particularly eccentric incident. To bring the whole city together to respond to the dangers of the plague he organized a huge carnivalesque procession, during Diwali. That year, the procession would depart from the traditional Hindu and Muslim neighbourhood routes and instead go through those alleyways that had spruced up its streets and homes the most. Reportedly 6000 truckloads of garbage were removed and thousands of rats trapped. Priests in temples took the lead to clean up their precincts. During the procession itself, after the usual cavalry parade, the float of Laxmi, the goddess of cleanliness and wealth, came an unusual performance. It included wails of despair accompanied by scenes of a broken city, and models of huge rats, which was immediately followed by a float in which the spotlessly attired city cleaners and workers marched in like warriors along with civic officials, the mayor and Geddes himself in Maharaja costume, clearly locating the onus of cleanliness on the right shoulders.

For Geddes, a city is not “just a place in space, but also drama in time” – and his methodology and desire to directly engage with both these dimensions was something far ahead of his times. He knew that the spirit of urban planning lay in the spirit of the people and the ethos that infused their habitats. His ethnographic eye looked deep into the contours of the physicality of a city and perceived the inner arrangements that shaped it – whether cultural or economic.

What makes Geddes 1918 plan for Indore seem so cutting edge and progressive even today was that it was imbued with his deep interest for its people and his profound belief that a city’s plan for the future can only emerge from an understanding of its past. If a century ago Geddes could look at a city like Indore from a non-colonial perspective, and appreciate its inner strength and potential, what prevents today’s planners, developers and policymakers from emancipating themselves from the dominant globalized narrative of the smart-city?

The article was first published here as a part of the fortnightly column 'Place, Work, Folk' for The Hindu.