Why India should reject China's obsession with bigger, denser megacities

Why India should reject China's obsession with bigger, denser megacities

The world is in awe of China’s relentless capacity to produce gargantuan cities, each outdoing the most recent superlative that describes its predecessor. If Shenzhen and Shanghai are megacities, and the Pearl-River Delta a sprawling urban agglomeration, then what should we call the 130 million-strong Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei city-region the government is currently planning? A gigacity?

While China just keeps building bigger and higher, India has also supersized its old colonial cities, following the centripetal model of dense cores and endless peripheries. White collar workers in Delhi or Mumbai, just as in Beijing or Shanghai, are pushed out to new dormitory towns, hours away from their jobs. A part of the Indian working class may have managed to remain close to their place of work, but at the price of being squeezed into insecure, under-serviced settlements.

Millennium prophecies about the irrelevance of cities – thanks to new transport and communication technologies – have been buried along with countless urban utopias. Cities seem to be more central to the global economy than ever. For China and India, urbanisation and development have become quasi-synonymous. In 2012, China’s real estate and construction industry accounted for 15% of the country’s GDP. In India, Mumbai’s represents about 20% of the country’s GDP, and 60% of it is produced in urban areas.

Yet, as far as country-wide urbanisation is concerned, India appears to be lagging behind. The urban population of both countries was 26% in 1990. While this ratio changed only marginally in India, it doubled in China. The UN predicts that it will take at least another 35 years for India’s urban population to reach China’s present 54% mark. By which time, the global giant will be respectably urbanised with three-quarters of its population living in cities and towns.

India seems desperate to catch up with China when it comes to urbanisation. The government plans to create 100 or so “smart cities”, wired to the world and connected to each other via new airports and high-speed trains. New York’s Bloomberg Philanthropies, among others, are advising the government on what being “smart” is all about when it comes to city planning.

But is urban growth really comparable between India and China? And can the shift from rural to urban be expressed only in terms of residential statistics?

One of the main differences between the two countries is the way they deal with internal migration. China has official restrictions on its workforce. It tries (and fails) to maintain its district boundaries through sharp control of movement. In contrast, India’s working classes and service providers move from city to city, village to village, rural to urban areas with astounding fluidity and frequency.

The unacknowledged armature of pan-India’s urbanity is its run-down railway network, which carries 9 billion passengers per year – four times as much as China’s state of the art network does. This difference is partly explained by the price: the cheapest train ticket from Shanghai to Beijing (1,318 km in 12 hours) is about £33; from Mumbai to Delhi (1,442 km in about 18 hours), it is just above £3.

Contrary to the common belief that people are simply moving from rural to urban areas, another scenario is playing out in India. Trains and buses going back to the hinterland are just as crowded as those going towards the big cities. There is massive multi-directional traffic of people moving perennially up and down the country. This movement is part of a deferred commuting pattern in which the village and the city are both active spaces in people’s personal and professional lives.

It is typical for an urban worker in India to return home twice or three times a year – for family functions or to help with the farm during monsoons. Urban families with strong roots in villages have also diversified their sources of revenue and reinvested money there. Millions of small projects are taking place in India’s villages as people build new homes, develop local infrastructure and invest in new technologies for farming and small-scale manufacturing.

With connectivity and infrastructure catching up, villages are turning into more than safety nets for rural-urban migrants. They are becoming parts of large urban systems, where many Indians project their future – even if that future is made of journeys back and forth.

It is true that migrants to cities have contributed to India’s urban growth. It is equally true that they have maintained ties with their native village homes. Family structures have adapted to manage long-distance relationships. Thanks to mobile technologies, running dual households is easier than ever before – and partly explains the enthusiastic absorption of this technology; indeed, 650 million Indians are slated to be smart phone owners in four years from now.

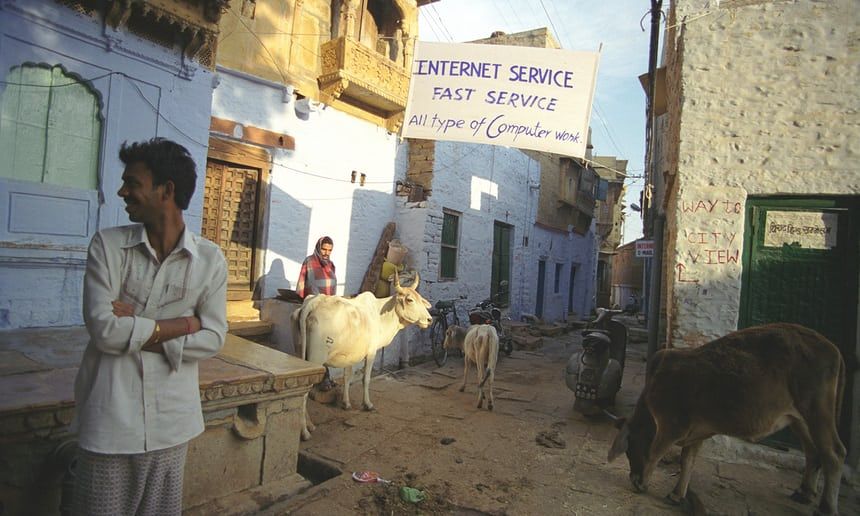

Smart phones allow urban Indians to remain in touch with their rural homes, facilitate economic transactions and contribute to the diffusion of urban lifestyles all over the country. It is not just the settled middle-classes that are wired and mobile. The vast majority of workers and service providers, who sell ware on the streets and live in shanties, are also part of this process. A large, though unaccounted, share of the 24% urban dwellers who live in slum areas have kept active ties with their ancestral villages.

India’s brand of “circulatory urbanism” differs from the standard 20th century model of dominating cities and an endless periphery. Its networked habitats and lifestyles are not quite suburban or simplistically rural either, since dual households remain economically productive and socially relevant on both ends of the spectrum. The same person shifts worker status, slipping from farmer to driver, shopkeeper to manufacturer, hopping between activities and habitats – and confusing census data.

This is not to say that cities have become irrelevant. On the contrary, they remain key nodes in ever expanding regional and global networks. At some level, cities have always played that role. Mumbai grew as a colonial trading hub, where resources taken from the hinterlands where shipped to the rest of the world. What is new is the level of connectivity between rural and urban zones, generated by people’s free movement and communication. These movements, which ultimately question classic notions of the urban and the rural, are an essential component of India’s urbanity. This means that urbanisation can’t be reduced to a milestone on a demographic chart.

In fact, it would make better sense for policies to forsake the arcane rural and urban lines of directing investment and recognise that India’s urbanity lies on the points of connections between these abstractions. India is more networked than we care to acknowledge. A shift in perspective will help evolve a set of categories and projects that do greater justice to the emerging urban landscape in India.

At present, census data tells us that the fastest urbanisation is happening in smaller towns and cities all across the sub-continent, which are yoked through active channels of mobility to large metropolitan hubs. However, these small and mid-size towns are not just growing in terms of population, but are active nodes that sit on various criss-crossing channels – linking villages and towns.

Such towns have harnessed the increase in movement brought by advances in transport and communication over the last decades. Urban planners in India need to work with their flows and circulatory systems. For example, recognising the needs of a mobile population, and encouraging the production of affordable rental accommodation in cities in a more targeted way of reducing slums compared to most policies in practice today.

Factoring in how the to-and-fro movements of labour shape urban and rural landscapes through families that work as dispersed but connected units will go a long way in planning more appropriate infrastructure for the real needs of people everywhere.

In the long run, if we are at all serious about addressing environmental concerns and balancing different modern economic sectors – including the agrarian – in a labour-surplus economy, then remapping the interconnections between the rural and the urban will make it easier to achieve those objectives.

It is time we start conceiving of the urban as a realm that stretches far beyond the discrete unit of the city – smart or otherwise. Most present policies will only create small enclaves of medieval style fort-cities, surrounded by vast expenses of undervalued habitats.

Instead of playing the catch-up game with China, and exhausting itself on the stationary treadmill of urban development, India should probably recognise the potential of its own brand of user-generated urbanism. Rather than high-speed, it may need to invest more in keeping trains and roads accessible to ordinary residents in villages and towns, as well as big cities.

It is time to get over an outdated image of cities as prime markers of urbanisation and progress in pure demographic terms. India may well be urbanising in ways that are potentially far more sustainable and contemporary than those it is trying to emulate.

This article was first published in the Guardian.